This year marks 100 years since Malcolm X was born, in Omaha, Nebraska. His 1964 visit to Ibadan helped solidify his transformation from racial separatist to global human rights advocate.

Who Was Malcolm X?

Malcolm X was born on May 19, 1925. His father was found dead when he was just six years old, allegedly murdered by white supremacists. His mother was overwhelmed with raising seven children and little money and subsequently suffered a mental breakdown. Young Malcolm would be placed in foster care, where he experienced what he later called “the terror of the very white social workers.”

Despite being a good student, a defining moment came when his favourite teacher asked about his career aspirations. When Malcolm replied that he wanted to study law, the teacher responded with a racist slur and told him that his aspiration to become a lawyer wasn’t a realistic goal “for a boy like him.” This crushing experience led to his academic decline and eventual descent into petty crime.

At 20, Malcolm was imprisoned for burglary. It was while behind bars that he discovered the Nation of Islam (NOI) and its leader, Elijah Muhammad. The NOI’s taught that Black people were inherently good children of God while white people were “devils”. As he later wrote: “Here is a Black man caged behind bars, probably for years, put there by the white man… That’s why Black prisoners become Muslims so fast when Elijah Muhammad’s teachings filter into their cages.”

Released in 1952, Malcolm became the NOI’s most powerful spokesperson. He rejected what he described as his “slave name,” Little, for the surname X for which he is now known. For over a decade, he preached that white people were devils and fiercely opposed integration. This put him at odds with Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil rights movement. He dismissed King’s famous I Have a Dream speech, declaring: “No, I’m not an American. I’m one of 22 million Black people who are the victims of Americanism… I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare.”

1959: His First Visit to Africa

Malcolm X’s worldview began to shift dramatically through his exposure to international politics and Pan-Africanism. The 1954 Bandung Conference brought together Third World nations regardless of race to oppose imperialism. It challenged his idea that black people couldn’t cohabitate with whites. At this time, he had also begun growing his knowledge of traditional Islam. Unlike NOI, traditional Islam emphasised equality and brotherhood of all believers. This ultimately created tension with the NOI’s race-based theology. And he found it difficult to reconcile both.

In 1959, the 34-year-old Malcolm X made his first trip to Africa as an ambassador for the Nation of Islam. Travelling in his new name, Malik el-Shabazz, he visited Sudan, Nigeria, Egypt, Ghana, Syria and Saudi Arabia. The goal of the trip was to arrange a tour for Elijah Muhammad rather than public engagement. It, however, opened Malcolm’s eyes to a world beyond America’s racial divisions.

His travel diaries from this period reveal his fascination with African civilization and his growing connection to the continent. Sudan’s ancient Nubian civilisation was of particular interest to him as was the anti-colonial legacy of figures like Muhammad al-Mahdi.

1964: His Second Visit to Nigeria

In March 1964, Malcolm X broke with the Nation of Islam, became a traditional Muslim and completed his pilgrimage to Mecca. His experiences in Mecca, where he witnessed Muslims of all races worshipping together as equals, had shattered his belief in the inherent evil of white people. He was now ready to build international solidarity against oppression rather than racial separation. It was in this spirit that he embarked on his most significant African journey.

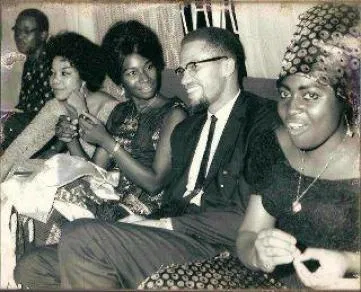

Malcolm X arrived in Nigeria on May 17-21, 1964, as part of a broader African tour that would reshape his understanding of the global struggle for human rights. His most significant engagement was at the University of Ibadan. There, he delivered an electrifying speech at Trenchard Hall that left a lasting impression on Nigerian students and intellectuals.

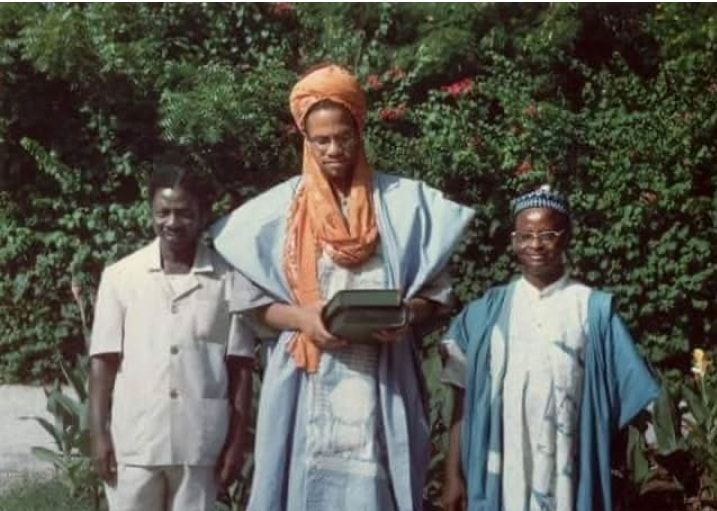

During this visit, the Muslim Students’ Society of Nigeria (MSSN) honoured Malcolm X with the Yoruba name Omowale, which translated to ‘the child has come home.’ This ceremony moved him deeply, and he would later describe it as one of the highest honours of his life.

Speaking in Accra, Ghana, shortly after leaving Nigeria, he reflected on this moment with elation:

“When I was in Ibadan at the University of Ibadan last Friday night, the students there gave me a new name, which I go for, meaning I like it. ‘Omowale,’ which they say means in Yoruba, if I am pronouncing that correctly, and if I am not pronouncing it correctly, it’s because I haven’t had a chance to pronounce it for four hundred years, which means in that dialect, ‘The child has returned.’ It was an honour for me to be referred to as a child who had sense enough to return to the land of his forefathers, to his fatherland and to his motherland. Not sent back here by the State Department, but come back here of my own free will.”

The name and the reception was for Malcolm X, a homecoming that validated his evolving identity as part of a global African diaspora rather than merely an American civil rights leader.

His Thoughts And Observations on Nigeria

During his Nigerian visit, Malcolm X conducted interviews and interacted with local communities. His observations revealed both admiration for the Nigerian people and sharp criticism of American influence in the region. In one interview, he praised the natural beauty and richness of Nigeria while highlighting the stark contrasts he witnessed.

“Nigerian people are hospitable and brotherly,” he observed, but added that: “U.S. influence has turned Nigeria almost into a colony; conditions are explosive, with elections that could turn Nigeria into another Congo.”

This was in1964, just before the federal elections.

The poverty he witnessed in Lagos, which he contrasted unfavourably with Ghana’s more evident progress, struck him. “Nigeria is one of the richest countries on the African continent, one of the most beautiful of the African countries. But by the same token you’ll find beggars there, you find poverty there. You don’t find new cities. You find beggars and poverty in Lagos, which you don’t see in Ghana.”

He also identified systematic problems: “I think Nigeria’s problems stem primarily from the over-exertion on the part of outside interests. The United States presence in Nigeria is far beyond what it should be, and its influence is far beyond what it should be.”

Dreams of Afro-American Unity

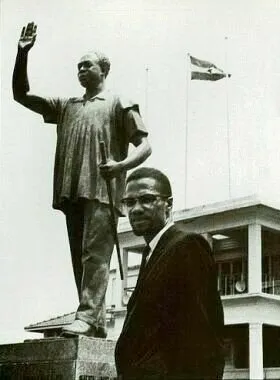

Malcolm X’s experiences in Nigeria were part of a larger transformation that would define his final year. His African travels, including meetings with leaders like Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, convinced him that the struggle of African Americans was part of a global movement for human rights and decolonization.

The warm reception he received in Nigeria, particularly the naming ceremony, reinforced his belief that African Americans needed to understand their struggles within an international context. As he put it in a December 1964 interview:

“Those who are invited are able to see that the problem of the Black people in this country is not an isolated problem. It’s not a Negro problem or an American problem. It’s part of the world problem. It’s a human problem.”

This insight led to him founding his Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) in June 1964, modelled after the Organization of African Unity. The goal of the OAAU was to take the case of African American human rights violations to the United Nations by leveraging the solidarity Malcolm X had witnessed in Africa.

On February 21, 1965, only a few months after his visit, he was assassinated. At this time, he was already working to build precisely the kind of international solidarity he had experienced in Nigeria and around Africa. The warmth and wisdom he encountered in like Ibadan helped catalyze his transformation from a black separatist to a global human rights advocate.