In 1964, the founding Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, undertook a 35-day journey across 17 African countries, including Nigeria. He returned with a clear vision of how not to run a newly independent country. This vision would shape the rise of Singapore.

From Singapore to Africa

At the time, Singapore was still a part of Malaysia and amid the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War Indonesia’s president at the time, President Sukarno, was opposed to the newly formed Federation of Malaysia. Lee had visited to seek support for the federation from the newly independent countries. The trip allowed Lee to meet and engage the leaders of the newly independent African nations.

This period was marked by many African nations rejecting capitalism and ideas of free trade. They associated it (among other things) with colonialism and imperialism and adopted its opposite, socialism wholesale. Socialism involved nationalizing industries, government control of prices, imports and foreign exchange and often autocratic governments. In the case of Tanzania and Ethiopia, it meant forcing people out of their homes onto villages.

In fact, Western institutions actively supported many of these experiments. The World Bank, USAID, the U.S. State Department and even development economists from elite institutions like Harvard lent legitimacy, funding and intellectual cover to policies that nationalized industries, fixed prices and centralized planning. These institutions viewed state control as a fast track to modernization and stability in postcolonial societies, especially in countries seen as bulwarks against communism.

Lee viewed Africa’s widespread embrace of socialism which was often justified by colonial exploitation or appeals to African traditions, as a path that led to avoidable poverty. In his words, “I was not optimistic about Africa.”

Tanzania

In a 2001 interview with PBS, Yew recalled his experience in Tanzania during his visit, and his interactions with Julius Nyerere, its first president. In his words: “Oh, yes, Julius Nyerere is a good Christian. He wanted to do good to his people. He’s a great Christian; he can quote you chunks of the Bible. He was a preacher also. He was a devout Catholic. But he didn’t understand the economics of growth, or just simple economics.

“He thought if you gather people together — I think it’s called “ujamaa,” or some form of communalized agriculture. So he had them all in villages, and they would work their farms. And then they were living together, and the children would go to school, and you can provide health services and so on. It’s the noble objectives. But walking back and forth to your farm, there’s nobody to look after them and so on, and then you have cooperatives that buy the products at uncompetitive prices, so whole thing malfunctions. It was a terrible waste.”

In 1967, Tanzania’s ruling party’s Arusha Declaration nationalized banks, insurance companies and foreign trading companies. From 1973, the Tanzanian government forcibly loaded about 13 million peasants into trucks and relocated them to roughly 8,000 ‘co-operative villages’ to participate in communal food production and marketing. All in the spirit of Ujamaa. The process was gruelling and many lost their lives. Nyerere went further and bulldozed abandoned homes to pre-empt their owners returning. All crops produced by these artificial villages were to be bought and distributed by the government. It was illegal for the peasants to sell their own produce.

Nyerere would leave Tanzania one of the world’s poorest countries, a status it still retains till today. As of 2024, about 49% or 26 million Tanzanians live below the poverty line.

Nigeria

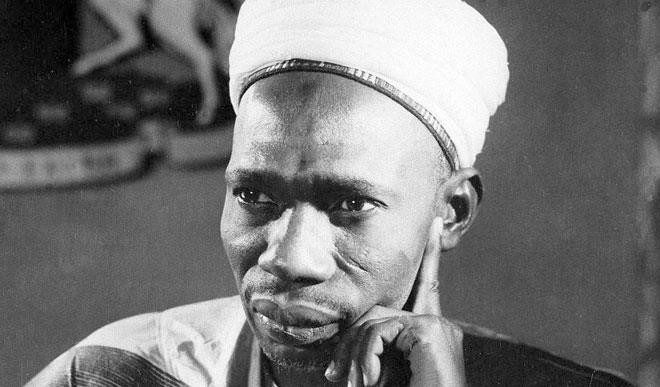

At the time of his visit to Nigeria, the Prime Minister, Sir Tafawa Balewa made a strong impression on Lee. The spectacular guard of honour welcome ceremony he received coloured Lee’s impression of Balewa. It was all done in the manner of the British. There was also the infrastructure of Lagos at the time, which looked very much like that of the British.

Balewa was a renowned Anglophile. Lee found this imitation of the British rather disingenuous. In his view, embracing the Western way without question or adaptation was as dangerous as rejecting it entirely. But this was in secondary significance to what he saw as Nigeria’s peculiar problem, tribalism. He noted that Nigeria’s political power was given by the British to the northern Nigerian Muslims. This created the feeling of exclusion and marginalization among the Christian south.

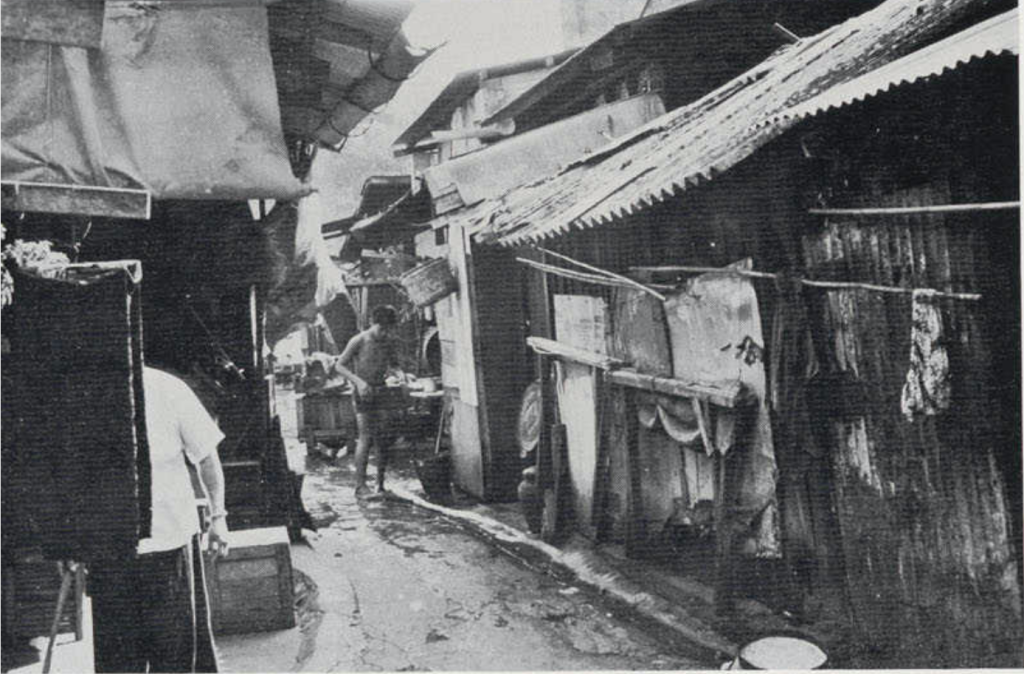

Two years later, in January 1966, Lee returned to Lagos for the first Commonwealth meeting, which Balewa hosted to coordinate efforts against white-minority rule in Rhodesia. According to Lee, Lagos looked like it was “under siege.” Police checkpoints lined the road to the Federal Palace Hotel, where Balewa was hosting a banquet for his guests. Barbed wires and troops surrounded the hotel and none of the leaders present left the Hotel throughout the two-day conference. These were signs of the tensions brewing at the time that would lead to the coup and ultimately devolve into the Biafran Civil War.

Reflecting on his visit, Lee would recall in his memoirs: “I thought their tribal loyalties were stronger than their sense of common nationhood. This was especially so in Nigeria, where there was a deep cleavage between the Muslim Hausa northerners and the Christian and pagan southerners.” His haunch about was correct. Just three days after the meeting, army majors from the Christian south assassinated Balewa was assassinated in a coup.

Ghana

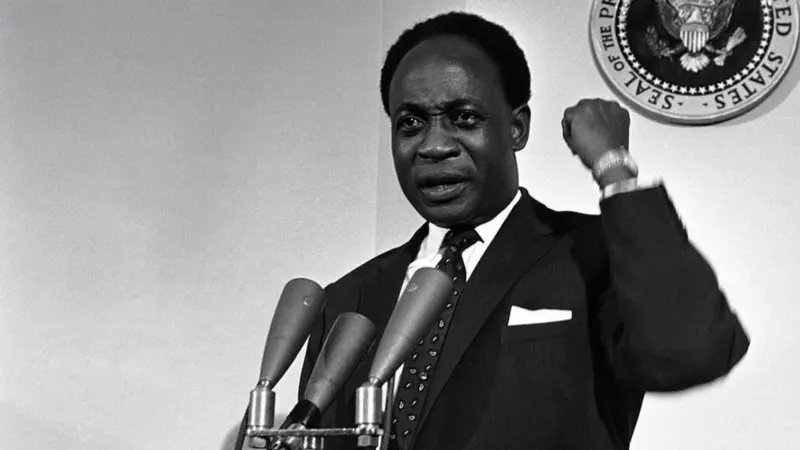

After leaving Nigeria, Yew’s next stop was Accra, Ghana. News reached him three days later that a coup had been carried out in Lagos, and that Balewa had been killed. In Ghana, he met President Kwame Nkrumah, a charismatic leader who had founded Ghana’s first republic in 1960.

Nkrumah’s vision for Ghana was ambitious. He wanted to rapidly industrialize the nation to reduce its dependence on colonial trade systems. His government embarked on extensive development plans. The most prominent was the construction of the Akosombo Dam, which provided hydroelectric power and was central to his economic strategy. However, these projects were financed through significant borrowing that led to mounting national debt.

By 1964, Nkrumah had introduced a Seven-Year Development Plan that focused on further industrialization. He founded 64 state corporations. However, the implementation faced challenges, including lack of capital and underestimation of the complexities of managing state enterprises. The period saw an explosion in corruption, rising unemployment and a decline in agricultural productivity. At the time of the 1966 coup that removed Nkrumah, to great jubilation across Ghana, only 3 or 4 of his 64 state enterprises were profitable.

Due to his visit, Lee Kuan Yew observed the consequences of Nkrumah’s policies first-hand. He noted that while Nkrumah’s intentions were noble, it lacked pragmatism. Also, he was certain that endemic corruption he witnessed first-hand during the visit and economic mismanagement would inevitable lead to the failure of Nkrumah’s policies. He left Ghana with his belief in the importance of meritocracy, economic pragmatism and incorruptible governance reinforced.

Nigeria and Ghana were two countries he considered ‘the brightest hopes of Africa’. But they both let him down as they did many millions of Africans. Speaking of Ghana, “My fears about Ghana were not misplaced. Notwithstanding their rich cocoa plantations, gold mines, and High Volta dam, which could generate enormous amounts of power, Ghana’s economy sank into disrepair and has not recovered the early promise it held out at independence in 1957.”

The Singapore Way

Whereas Julius Nyerere seized foreign-owned banks and plantations, Lee Kuan Yew rolled out the red carpet for multinational corporations. He understood that Singapore, with no natural resources, could only thrive by becoming the world’s most business-friendly economy. Instead of demonizing foreign investors as neo-colonialists or imperialists and seizing their businesses, he courted them aggressively. Lee didn’t just allow foreign companies, he begged them to come. He lured American, European and Japanese firms to Singapore with tax breaks, world-class infrastructure and a corruption-free bureaucracy.

Within three decades, Lee had transformed a former British colonial backwater into the ranks of New York, London and Switzerland. By 1965, Singapore’s per capita GDP was just around US$500. Today, it’s at a staggering US$55,000.

The Singapore Way Inspired China’s Growth

While Africa saw a succession of radical ideas, Lee never had any ‘philosophy’ or ‘ideology’ of choice. Often quoting Deng Xiaoping who famously stated: “It doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice,” he followed what worked.

Yet, those words could have been Lee’s for Deng himself was influenced by Lee.

In the late 1970s, as China faced economic stagnation and social upheaval following the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping studied Singapore’s remarkable transformation. He visited in 1978 and saw in Lee’s model a blueprint for China’s own survival. Lee’s disciplined governance, openness to foreign investment and commitment to meritocracy impressed Deng deeply. Upon his return, Deng launched China’s historic ‘Reform and Opening Up,’ invited foreign capital, decentralized the economy and rolled back communist orthodoxy in favour of practical development.

In this way, Lee’s Singapore helped inspire China’s great economic turnaround and the shift that lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty and placed China on the path to becoming a global superpower.

Lee avoided the injustices of the past from running the promise of a great future for Singapore. For instance, despite feeling betrayed by the British during World War II who had not defended Singapore against the Japanese, Lee sought their continued military presence in Singapore post-independence. This was to counterbalance the fear that the Chinese would seize the island, a fear that played a role in Singapore being expelled from Malaysia.

This decision was one of too many where Lee showed his commitment to safeguarding Singapore’s future and prioritizing developmental goals over past grievances. Lee’s leadership exemplified a focus on practical outcomes, that allowed him to steer Singapore toward stability and prosperity through adaptable and effective policies.

“I was not optimistic about Africa.”

Lee Kuan Yew’s 1964 African tour gave him of first-hand view of the pitfalls of adopting ideologically charged policies without considering practical economic realities. As Lee saw it, “To rally their people in their quest for freedom, the first-generation anti-colonial nationalist leaders had held out visions of prosperity that they could not realize.”

Lee’s experiences and interactions with the new African leaders taught him priceless lessons on the importance of effective governance, economic pragmatism and national unity. These lessons would profoundly impact Lee’s approach to developing Singapore. They taught him the need to emphasize meritocracy, to embrace a market-driven economy and to encourage foreign trade.

The subsequent transformation of Singapore into a global economic powerhouse owes, in part, to these lessons well learned. African leaders can return the favour by learning from Singapore’s successes.