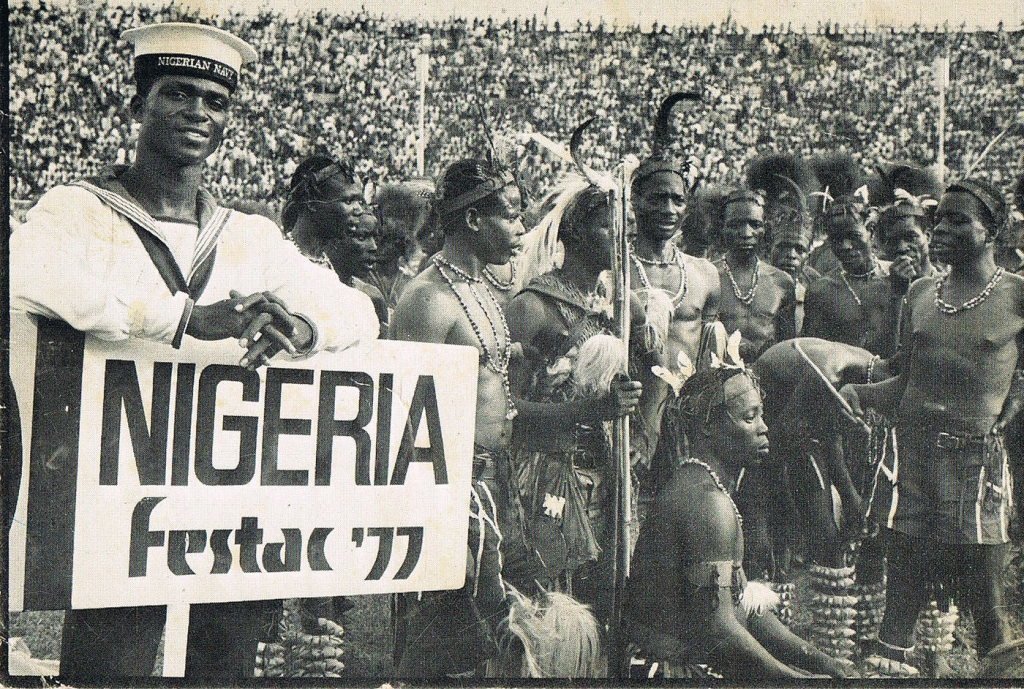

The 1970s were Nigeria’s golden years. For a decade, thanks to high oil prices, Nigeria was one of Africa’s richest countries per capita. The naira’s value was higher than that of the dollar. In the famous words of the Head of State at the time, General Yakubu Gowon, “Money is not Nigeria’s problem. But how to spend it”.

However, the party would abruptly end in 1982 when oil prices came crashing down. The reforms that followed saw Nigerians suffering like never before. Fast-forward to Tinubu’s government and it feels like the 80s all over again.

The 70s Were Nigeria’s Golden Years

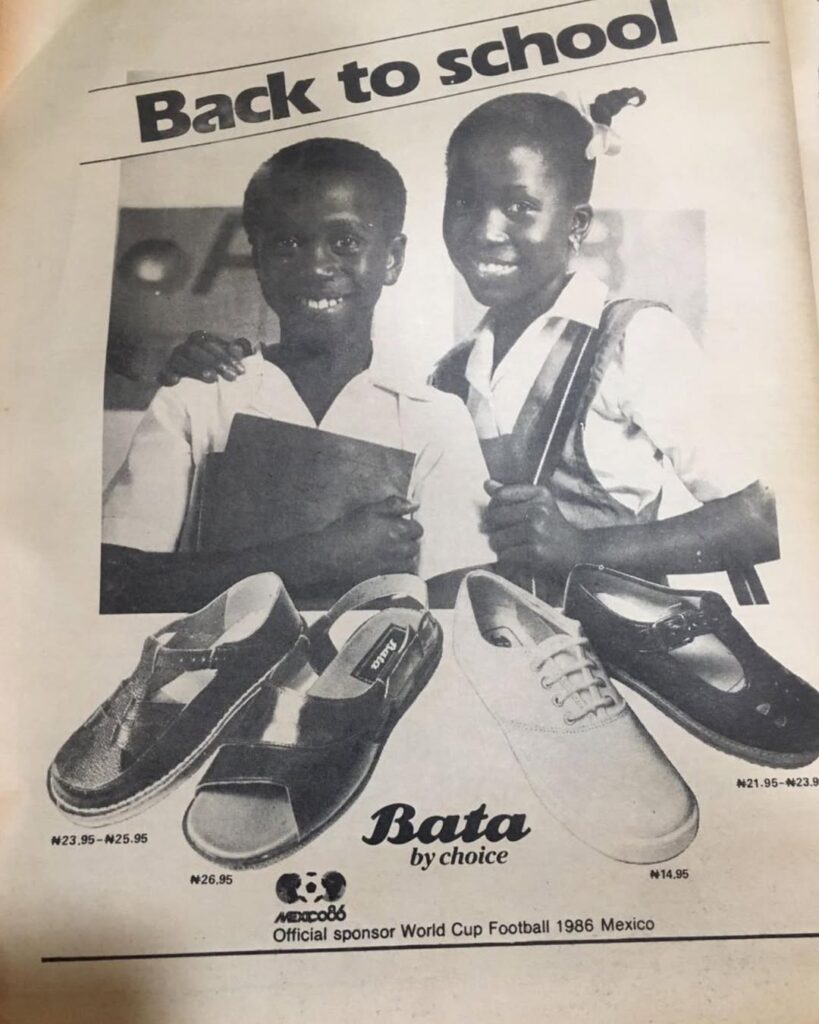

Following the 1973 oil embargo instituted by OAPEC against Western nations supporting Israel during the Yom-Kippur War, global oil prices quadrupled from $2.90 to $11.65 per barrel. Nigeria, having joined OPEC in 1971, benefitted from this surge. For a decade, thanks to these high oil prices, Nigeria was one of Africa’s richest countries per capita. Oil production skyrocketed and government revenues exploded. GDP surged from about $12.6 billion in 1970 to $164 billion by 1981. Per capita income soared from $245 in 1970 to $1,025 by 1980. The naira was more valuable than the dollar, exchanging at around 0.6 naira to the dollar. True to his words, Gowon went on a spending spree, building roads, universities, hospitals, office complexes, army barracks, hotels, factories, etc.

With this influx of petrodollars, Nigeria created an economy with government at its centre. The state seized the “commanding heights” of the economy; it took control of schools banks, created mega parastatals left and right and nationalized existing plants like Shell’s refinery in Port Harcourt. The government warehoused all foreign currencies and became the sole dispenser of forex through import licenses obtained from bureaucrats.

But beneath the surface, trouble was brewing. The oil windfall flowed almost entirely to government coffers and the elite connected to it. Oil gas grew to account for over 95% of Nigeria’s exports and roughly 80% of federal revenue. The government severely neglected agriculture and manufacturing and the iconic groundnut pyramids slowly disappeared. The agriculture sector, which up till then accounted for up to 50% of Nigeria’s GDP and 64.5% of export, died off.

Babangida’s Structural Adjustment Program

The party ended abruptly in 1982. What the IMF described as a “double whammy” of collapsing oil prices and rising global interest rates hit Nigeria. Oil prices plunged back to $2 per barrel, inflation began to climb and our foreign reserves dived. The regimes of Shagari and Buhari responded with austerity measures, reduction in government spending, banning importation and instituting price controls. In a rage of blame-game, Shagari issued an order expelling all undocumented immigrants, leading to the infamous Ghana Must Go.

Nigeria traded essential commodities for oil, then shared them in what became known as “essenco”. Expatriates, or those of them who were not expelled, left Nigeria as did numerous Nigerian skilled workers. The health sector was particularly affected. Medical teachers and doctors began leaving for the West and the Middle East in search of better pay and career prospects

By 1985, the economy was in freefall with public debt mounting and foreign credit lines drying up. This crisis of confidence contributed to General Babangida’s military coup in 1983 that deposed Buhari, who had earlier deposed Shagari. In July 1986, after public debate on the subject, Babangida’s regime formally embraced an so-called Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP), as conditions for IMF and World Bank loans.

The reforms looked similar to those of Tinubu’s government:

The government floated the naira, first via a crawling peg and then a full market float in September 1986. This move will give rise to Bureau de Change of today, who received licences to trade forex outside the government’s own channels.

- Multiple exchange rates were unified

- Price controls were lifted

- The government removed subsidies on key goods (notably petrol and fertilizer)

- Trade and financial markets were liberalized

- Government gave up most of its state-owned enterprises and they were privatized or commercialized

Inflation soared from about 5.4% in 1986 to roughly 40.9% by 1989. Wages and real incomes collapsed and millions were pushed below the poverty line. The result was widespread popular anger: teachers, workers and professionals staged strikes in protest. Cases of looting and violence occasionally flared in cities. To help cushion the effect of this programme, the government instituted programmes like mass transit programmes, micro-finance banks and other programmes to boost agriculture in the rural area. Yet, by the end of the decade, the hopes promised in SAP remained unfulfilled.

Enter Tinubu’s Government: History Doesn’t Repeat, it Rhymes

Fast-forward to Tinubu’s government and it feels like the 1980s all over again. Within days of taking office in May 2023, President Bola Tinubu abruptly removed Nigeria’s long-standing fuel subsidy. He also liberalized the exchange rate, effectively merging Nigeria’s parallel markets and allowing the naira to depreciate sharply. In practical terms, the currency has lost well over half its value, falling from about ₦460 per USD in mid-2023 to around ₦1,700 by late 2024.

The economic prescription is virtually identical to Babangida’s 1986 formula: subsidy cuts, currency flexibility and liberalization. And just as in the 1980s, the consequences for Nigerians have been severe. Since mid-2023, inflation has surged, reaching roughly 30% (a 28-year high) by early 2024 with skyrocketing fuel and food prices, the main drivers. By June 2024, inflation had climbed to about 34%, with food inflation exceeding 40%.

After the subsidy cut, pump prices jumped from about ₦185 per litre in 2023 to ₦1,025 in 2024, while the naira plunged from ₦460 to ₦1,700 per dollar. These shocks have driven a sharp rise in poverty levels. According to Human Rights Watch, over 80% of Nigeria’s 200+ million people already live in poverty. Removing the fuel subsidy directly pushed them “into a desperate struggle to afford necessities”.

What History Teaches Us

The parallels between Nigeria’s 1980s SAP and the reforms of Tinubu’s government are unmistakable. Nigeria continues to be subjected to economic prescriptions that promise prosperity but deliver pain. According to Radhika Desai, the SAP programs of the 80s served primarily to transfer wealth from developing to developed nations while impoverishing local populations. In effect, they cost Third World countries two decades of development.

International institutions have praised the subsidy removal and currency devaluation as Nigeria’s salvation. Just as they actively pressured Nigeria in the 1980s, Nigerians are told to sacrifice today for tomorrow’s prosperity that many never come. History shows these reforms rarely deliver on their promises when the underlying structural problems remain unaddressed. True economic transformation requires more than market liberalization and austerity. It demands addressing corruption, diversifying the economy beyond oil and implementing genuine social protections. Otherwise, Nigeria risks a repeat of the decades of lost development experienced across the Global South, which followed the overhyped reforms of the 80s.