Twenty years in the making, the Aba Power plant is both a tragedy and a triumph.

A Tour of Aba Inspires the Dream

According to the Chairman of Geometric Power Group and founder of the plant, Professor Barth Nnaji, the story began with a visit in 2004. Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, then Nigeria’s Finance Minister invited the late James Wolfensohn, former World Bank President to visit Aba. She wanted him to witness first-hand the city’s economic potential.

Naturally, they marvelled at the typical sights of Aba: shoemakers, clothiers and manufacturers, small-scale innovators and large enterprises like Star Paper Mill. It was clear, however that their potential was shackled by an unreliable power grid. They approached Barth Nnaji, a professor of engineering who had successfully built a 22 MW emergency plant in Abuja in 2001.

“After the visit in 2004, the duo asked me to consider building a 50-megawatt power plant in Abia for manufacturers,” Nnaji later recounted. He didn’t hesitate. “I acceded to the request by Dr. Okonjo-Iweala and Dr. Wolfensohn. What the two did not realize was that my enthusiastic acceptance was because the plant would be located in Aba. This city has a special place in the heart and mind of every person interested in our country’s rapid progress. It is the home of indigenous manufacturing, innovation and entrepreneurship.”

The Vision for Aba Power Plant Is Set Into Motion

In 2004, Geometric Power Limited signed a memorandum of understanding with the Federal Government to build a power plant in Aba. A year later, in April 2005, Geometric signed the Aba concession agreement, also with the Federal Government that granted it the right to distribute power to Aba.

The project would be Nigeria’s first integrated power utility. Geometric Power Aba Limited (GPAL) would generate electricity and Aba Power Limited Electric (APLE) would distribute it. Licensed by the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC), the plan targeted a “ring-fenced” area, including Owerrinta, Osisioma and Ogbor Hill, where industries and households desperately needed relief from constant blackouts.

Nnaji’s passion had a personal, dimension. As a manufacturing professor in the 1990s, Professor Nnaji had abandoned a plan to build a vehicle parts manufacturing plant in Emene, Enugu. This was after his South Korean partners balked at the region’s poor power supply.

“After all, I had watched my former students from Taiwan and other places in Southeast Asia rush home to produce sophisticated auto parts and engines,” he recounted. “So, a large swath of land was purchased for this purpose, but when my South Korean partners visited Enugu, it became obvious that the project would not take off principally because of poor electricity. It was while I was thinking of how to help resolve the electricity problem in Ala Igbo that Dr. Okonjo-Iweala and Dr. Wolfohnson made the request.” he recalled. “The rest is history.”

The Struggle for Aba Power Plant Begins

The history of this dream, as Professor Nnaji would soon find out was a story of “tears, sweat and blood”. What should have been a swift victory for Aba became a battle against bureaucracy, greed and political interference. The project’s momentum faltered in 2013 when the Bureau of Public Enterprises (BPE) sold the Enugu Electricity Distribution Company (EEDC) to Interstate Electrics, a company promoted by Emeka Offor. It had done so without exempting Aba’s ring-fenced area. This violated Geometric’s agreements and sparked a legal firestorm. “The BPE indicated that Aba ring-fence was encumbered, yet it included Aba ring-fence in its bid,” a National Council on Privatisation (NCP) report later admitted, exposing the bureaucratic blunder.

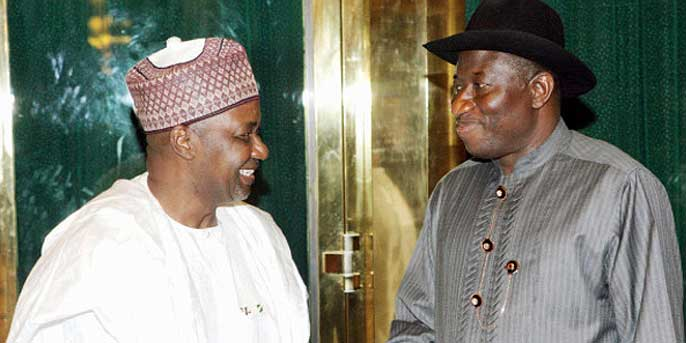

Then came the political machinations. Offor, a close ally of then-Vice President Namadi Sambo, wielded influence with the big man to protect Interstate’s interests. “The backing of former Vice President Namadi Sambo tilted the balance in favour of Offor’s Interstate Electrics,” sources noted, alleging that Sambo had vested interests in the company.

The NCP, led by Sambo, bent privatization rules and granted Interstate an extension to pay for EEDC after it had missed deadlines. This was clearly an act of favouritism that enraged analysts. “The sheer misanthropy that accompanies Nigeria’s version of barefaced political brigandage and patronage has left households and industries in entrepreneurial Aba… trapped under increasing blackouts,” wrote Lolade Akinmurele in a scathing 2024 critique.

Legal Battles Pile Up

Geometric sued to stop BPE from privatizing Aba’s distribution rights, while Interstate fought to join the fray. NERC, meant to regulate fairly, wavered under pressure from Offor and Sambo’s allies, including Pius Anyim, then secretary to the federation and Sam Amadi. President Goodluck Jonathan was kept in the dark with “spurious procedural and legal issues,” Akinmurele observed.

These delays bled Geometric dry. According to Nnaji, his firm paid $3.5 million monthly as interest on the $500 million borrowed. This was nothing short of a staggering burden for a $800 million project that included a 27 km gas pipeline.

Reports, however, piled up in Geometric’s favour. The NERC warned, “It will be a disservice to the country… to be denied the terms of the tripartite agreement.” The Ministry of Power urged respect for the 2004 lease.

All the while, Aba’s 2.5 million residents, its $200 million shoe and garment industry and countless livelihoods languished in darkness.

Light Shines At the End of a Very Long Tunnel

After nearly 20 years, the tide turned. By 2020, under President Muhammadu Buhari, the impasse began to unravel, though gas supply issues with Shell’s successor delayed progress further. Governor Alex Otti, upon taking office in May 2023, brokered talks with Geometric and NNPC to secure gas supply for the plant. On February 25, 2024, the first turbine hummed to life.

A day later, Vice President Kashim Shettima inaugurated the 181 MW plant. “The third turbine of the plant has been fired, and all three turbines are operational,” Otti announced, promising, “Power outage will be the exception rather than the rule.” Starting that weekend, Aba enjoyed 14 hours of daily power, a week ahead of schedule.

The plant now delivers 141 MW, expandable to 181 MW, across nine of Abia’s 17 local government areas. Its infrastructure, gas pipelines, transmission lines, and a new distributor, APLE, ushers in reliability. Residents jubilated as factories whirred and homes lit up. “Once Geometric Power addresses the electricity challenge… not even the sky will be the limit,” Nnaji declared, with visions of over 370,000 jobs and an industrial boom for his beloved Aba, the “Japan of Africa.”

The Game Was Worth the Candle

The Aba Power Plant’s journey is a tale of triumph shadowed by loss. “It has since 2004 been tears, sweat and blood,” Nnaji reflected, borrowing Churchill’s words. The 20-year delay, fuelled by “private greed and government ineptitude,” as Akinmurele put it, tells the story of “dark cloud over private investments” in Nigeria’s power sector. Systemic flaws, from cronyism to regulatory inertia, nearly buried a project that could have transformed Aba sooner. “The dark side of the Aba power project… leaves more to be desired,” Akinmurele concluded.

It’s almost impossible to argue with his assessment.

Regardless, though belated, Aba Power Plant’s completion is still a story of hope. Nnaji’s perseverance proves that determination can prevail even in the chaos that is Nigeria. Regardless, the plant’s success challenges Nigeria to reform: to shield projects from vested interests, streamline bureaucracy and honour its commitments.

The triumph of Aba’s power plant has the potential to spark a broader renaissance, but only if lessons are heeded. For now, the city glows brighter, in tribute to a visionary that refused to give up on his dreams.