The groundnut pyramids were once symbols of northern Nigeria’s wealth and economic power. Originally invented as a way to store groundnuts ahead of transportation for shipment, they became landmarks that defined a city and an era.

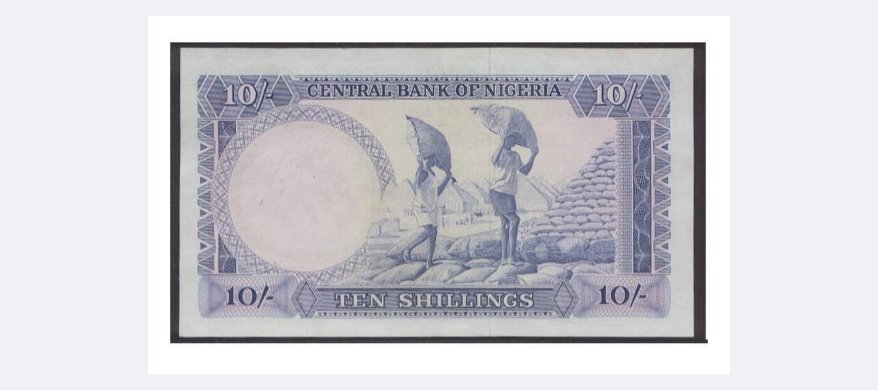

When foreign dignitaries visited, they were driven to see them. When the first naira notes, stamps and postcards were printed, the pyramids made it there ahead of other landmarks. But when the oil boom of the 70s came, they gradually disappeared to never be seen again.

Today, they exist only on faded photographs and in the memories of an older generation that saw the last glimpses of them. Here’s the story of what happened to them.

The Rise of the Pyramids

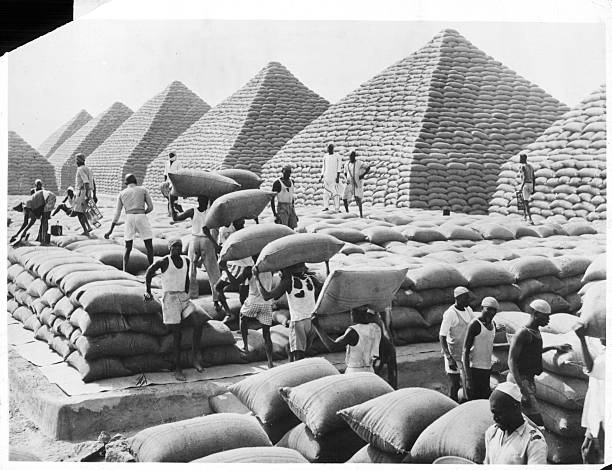

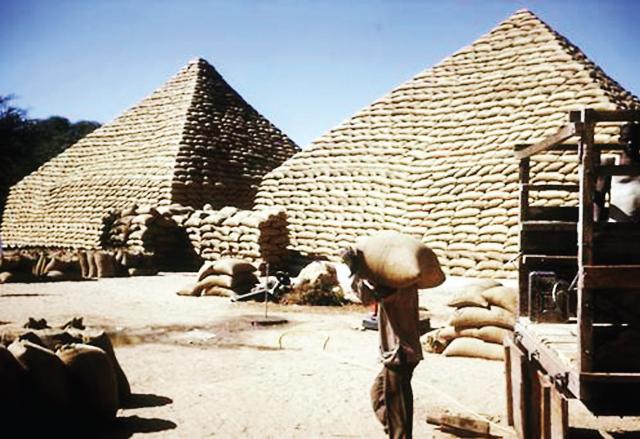

“When I was growing up in Kano, a large city in Northern Nigeria, peanuts were still a big cash crop,” recalls an eye-witness. “Kano was an export site, and the peanut bags waiting to be shipped out were stacked in the sun in huge pyramids, each pyramid holding 1000 tons of peanuts. A railroad ran strategically through the centre of the 60 or more pyramids. This was all located right in the heart of Kano, and the smell of fresh peanuts permeated the surrounding streets, mingling with the dust and oil and other city smells to make an unforgettable aroma.”

Alhaji Alhassan Dantata is regarded as the inventor of groundnut pyramids. In 1919, Dantata arrived in Kano from Kumasi, Ghana, where he was based, at the beginning of the groundnut boom. Within five years, Dantata had established himself as the primary supplier of groundnuts to the Royal Niger Company, the British firm that controlled much of Nigeria’s export trade. He would be licenced as a buying agent when in 1947, the British introduced a marketing board to regulate the groundnut trade.

Dantata, however, was faced with the challenge of storing massive quantities of groundnuts to await transportation via freight trains to Lagos for shipment. The pyramid system would be devised at his facility in Kofar Nassarawa, as a storage solution. His workers would stack the bags in a geometric pattern with each layer slightly smaller than the one below to create ‘pyramids’ that could contain up to 15,000 bags. Soon, these impressive formations became the trend. They started appearing everywhere across northern Nigeria—in Kofar Mazugal, Brigade, Bebeji, Malam Madori and Dawakin Kudu.

The pyramids became so iconic that when the first naira notes and postage stamps were minted, the groundnut pyramids featured prominently.

The Golden Era

Kano was already a commercial hub long before the colonial era. Its locals were engaged in various crafts like weaving, dyeing, embroidery and tanning. However, none of these crafts had the transformative effect that the groundnut trade would have on Kano. It was the groundnut trade of the 1950s and 60s that elevated Kano to international prominence. Merchants used the trans-Saharan trade routes to sell the product beyond West Africa to destinations like Ghana, Niger, Cameroon, reaching even Saudi Arabia.

Trains transported the groundnuts from Kano to Lagos, from where they were shipped to international markets. To make it easy to move them and return the wealth back to northern Nigeria, the pyramids were strategically positioned near the rail lines. The rail lines themselves, were built specifically to support the groundnut trade.

The pyramids were symbols of this prosperous era. They represented not just thousands of bags of groundnuts but also the labour of countless farmers across the northern region, the business acumen of local merchants and the efficiency of a well-organized agricultural system. It was the time when agriculture reigned supreme in Nigeria’s economy. Between 1960 and 1969, the agricultural sector accounted for over 50% of Nigeria’s GDP and generated 64.5% of export earnings. Then came oil.

How the Groundnut Pyramids Disappeared

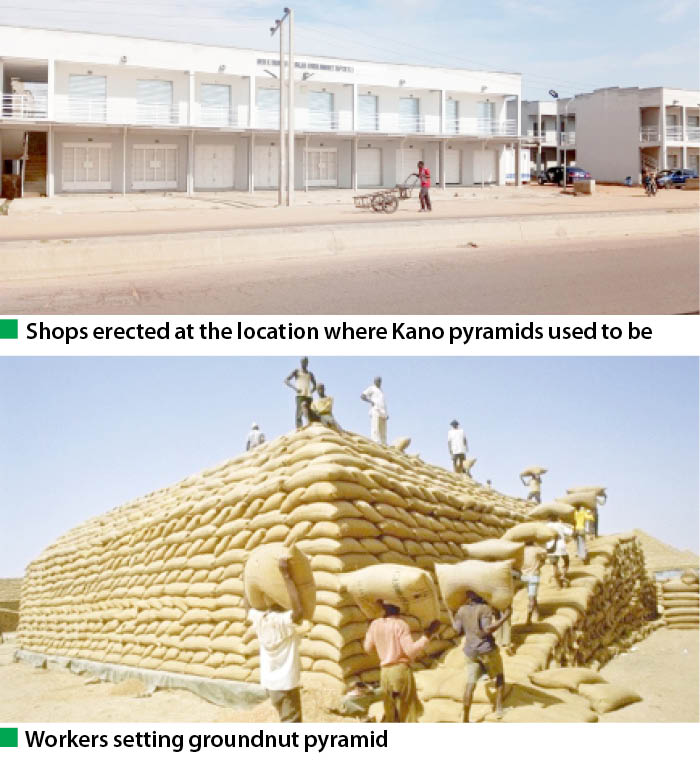

In 2014, National Mirror visited Kano and found no trace of these once-majestic structures. At Brigade Quarter, where one of the largest pyramids once stood, they found the moribund Kano Oil Mill. The site at Kofar Mazugal that once hosted those pyramids had become a driving school field by day and a hideout for miscreants by night. The Dan Agundi location now housed a bank building.

What caused this tragic disappearance? The answers are as complex as they are numerous.

You see, starting in the late 1960s, Nigeria underwent a transformation that forever changed its trajectory. The discovery of vast petroleum reserves in the country offered a seductive and a wealthier alternative to agricultural production. Oil promised quick wealth without the uncertainty of weather, pests, or market fluctuations that plagued the farming profession. And naturally, government attention and investment shifted dramatically toward this new and near inexhaustible resource.

Nature also played a cruel hand. Just as Nigeria was pivoting toward oil, a devastating plant eater, the Rosette virus disease struck the groundnut crops. In addition to these challenges was the dismantling of the railway system that had been the backbone of agricultural exports. This infrastructure that had made the groundnut trade possible crumbled at the time the industry needed it most.

There was also changing consumer patterns and industrial developments that displaced the product. There was also the rise of alternatives like cotton seeds and soybeans. Their competition contributed to the erosion of groundnut’s market position. By the 1980s, the pyramids had disappeared completely. Visit Kano today, and you’ll find no trace of these once-majestic structures.

In 2023, Daily Trust visited and found these:

What We Can Learn

It is fair to say that the pyramids haven’t disappeared but evolved. They now support agro-allied industries that use them as raw materials. However, while these changes surely played a role, the disappearance of Kano’s groundnut pyramids owes more than to just a change in agricultural practices or storage methods. It symbolizes a fundamental shift in Nigeria’s economic priorities and national identity.

Nigeria’s discovery of oil promised a quicker and stress-free path to wealth than the labour-intensive agricultural sector. It, however, quickly created a monolithic economy that was vulnerable to the volatile global oil market. Young people abandoned farms for cities in search of quick wealth in an economy flush with petrodollars. But oil wealth, unlike farming, failed to create prosperity for a vast number of the populace. The oil industry jobs were limited and specialized, unlike agriculture which employed millions across the country.

Unfortunately, this bliss that followed the discovery of oil, lasted for only a decade. Nigeria was dragged into two decades of immense suffering and instability when oil prices crashed in 1982. Yet, in response, Nigeria would do little to try to divest from oil. Ever since, all sorts of reforms have been touted and implemented but with our attachment to this cursed treasure still untouched.

But the great groundnut pyramids of Kano still remains in our collective memory as ghostly reminders of a prosperous agricultural past. More than that, they serve as silent admonitions about the dangers of putting all of one’s economic eggs in a single basket.

Building the Pyramids of the Future

Perhaps Nigeria’s future lies partly in reclaiming its agricultural heritage. This does not necessarily imply rebuilding physical pyramids as was done by the Ogun government with rice bags this time, in 2022 to much ridicule. It demands restoring the prominence of farming in our economic landscape. Yes, the pyramids may be gone, but the fertile soil that produced them still remains, waiting only for the right policies and new political visions to yield new prosperity.