Except for the rendition of Nnamdi Kanu in 2021, few stories from Nigeria’s history rival the audacious plot that unfolded on the streets of London in July 1984. It reads like something from a John le Carré novel: a kidnapping involving Israeli Mossad agents, Nigerian intelligence operatives, diplomatic crates and a man who had once been one of the most powerful figures in Nigeria, Umaru Dikko.

This is the story of how Nigeria’s most wanted man became the target of an extraordinary international manhunt that would strain diplomatic relations between Nigeria and the UK.

The Fall of the Second Republic

The story begins in the dying hours of 1983. Nigeria’s capital at the time, Lagos, was agog with New Year’s Eve celebrations. Beneath the festive atmosphere, however, lay a nation in crisis. President Shehu Shagari’s government was drowning in economic turmoil brought on by crashing oil prices, rampant inflation and accusations of widespread corruption. Allegations of massive rigging had marred the August 1983 elections, with opposition parties challenging results that kept Shagari’s National Party of Nigeria in power.

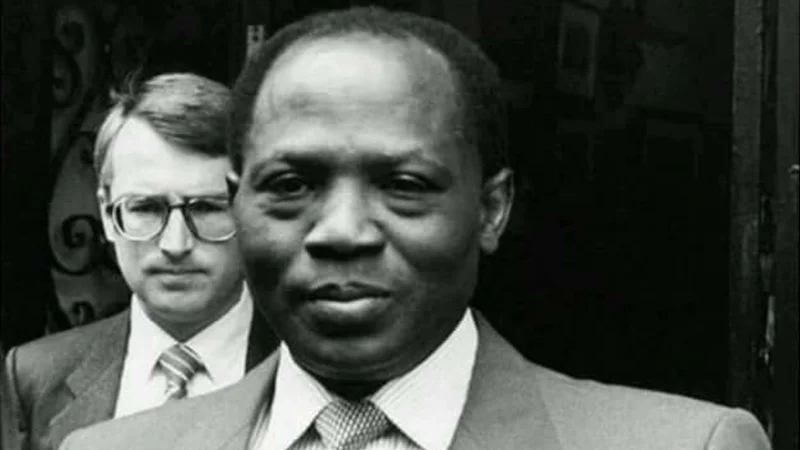

At the heart of this corrupt machinery was Umaru Dikko. He had served as the Transport Minister and later, Shagari’s campaign manager and brother-in-law. Born on December 31, 1936, in Wamba, Kaduna State, Dikko was the archetypal Nigerian politician of the 1980s. He was wily, flamboyant and utterly contemptuous of his critics. When challenged about the controversial election results which he had masterminded, Dikko had declared with characteristic arrogance: “Whether they [the opposition] accept or don’t accept the results is immaterial.”

As Nigerians partied into 1984, few could have predicted that within hours, martial music would fill the airwaves and bring the end of the Second Republic. Major-General Muhammadu Buhari’s coup had been swift and decisive. He Shagari’s government for what the military described as “inept and corrupt leadership, economic uncertainty and embarrassing levels of unemployment.”

By the time soldiers converged on Dikko’s official residence at 16 Alexander Avenue, South West Ikoyi, their most wanted quarry had vanished. The master manipulator had orchestrated his own escape, slipping through the Republic of Benin and Togo before boarding a KLM flight to London via Amsterdam.

Nigeria’s Most Wanted Man

In exile, Umaru Dikko proved as troublesome as he had been in power. From his hideout in London’s upscale Bayswater neighbourhood, he became the unofficial spokesperson for opponents of Buhari’s military government. He appeared regularly on British television and gave interviews where he harshly criticized the new regime and promised to bring it down.

Buhari’s government formally accused Dikko of looting the national treasury and embezzling billions of dollars in public funds. But the former minister’s television appearances and his vocal opposition to the military government only strengthened Buhari’s resolve to bring him home to face justice, by any means necessary.

What happened next would read like a Cold War thriller and featured an unlikely alliance between Nigerian intelligence and Israel’s elite Mossad operatives.

The Mossad Connection

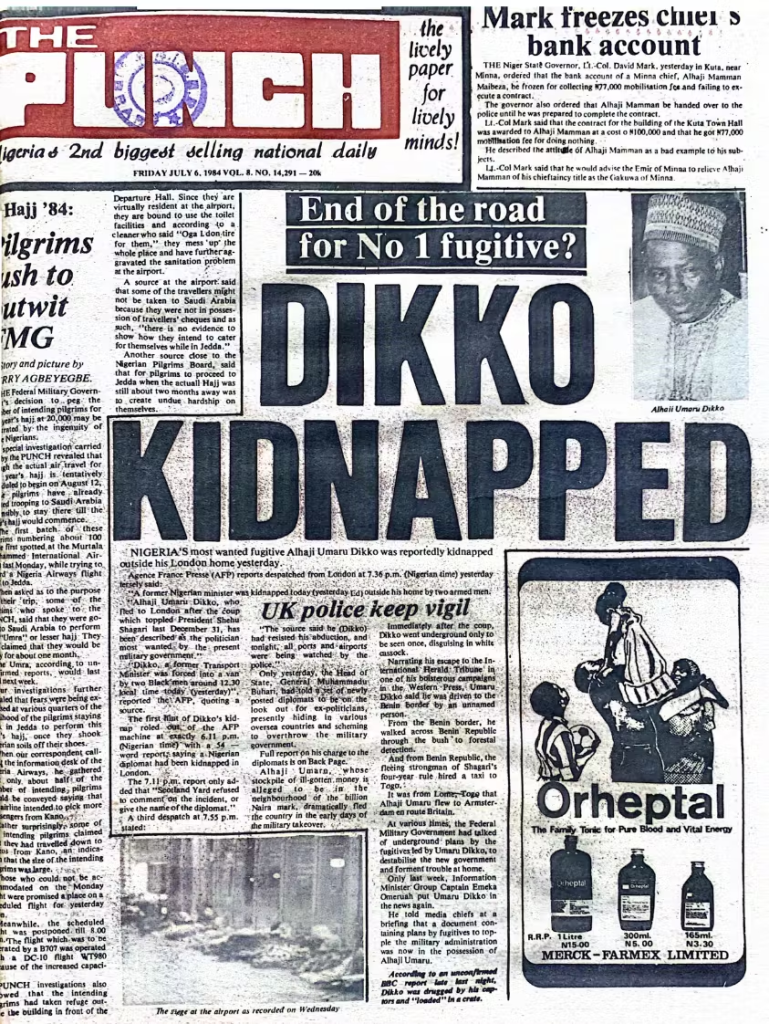

The plot to capture Umaru Dikko was a joint operation between Nigeria’s National Security Organisation (NSO) and Israeli intelligence. Mossad deployed undercover agents to London, tasked with locating and monitoring their target. On June 30, 1984, a Mossad operative spotted someone who matched Dikko’s description in Bayswater. For days, agents maintained constant surveillance, studying his routines and movements with the precision of professional hunters.

The kidnap team was led by Alexander Barak, a 27-year-old Israeli national and alleged former Mossad agent. His crew included Major Mohammed Yusufu, a Nigerian intelligence officer, Felix Masoud Abithol, a 31-year-old Tunisian-born Israeli, and Dr. Lev-Arie Shapiro, a 43-year-old Russian-born Israeli anesthetist from Tel Aviv’s Hasharon Hospital.

The plan was audacious in its simplicity: they would kidnap Dikko, sedate him, seal him in a specially designed crate and then smuggle him out of Britain as ‘diplomatic cargo’ aboard a waiting Nigerian Airways Boeing 707.

The Abduction

July 5, 1984, began as any other summer day in London. Shortly after midday, Umaru Dikko emerged from his house for his customary pre-lunch stroll. Within seconds, his world turned upside down.

“I remember the very violent way in which I was grabbed and hurled into a van, with a huge fellow sitting on my head – and the way in which they immediately put on me handcuffs and chains on my legs,” Dikko would later recall to the BBC.

Two men seized him and bundled him into a transit van. After navigating London’s streets, they transferred him to a waiting truck where Dr. Shapiro injected him with a powerful anesthetic, rendering him unconscious. The kidnappers then switched vehicles near London Zoo before heading to Stansted Airport, where their Nigerian Airways flight waited.

But there was a fatal flaw in their meticulous plan: Dikko’s secretary, Elizabeth Hayes, had witnessed the abduction from a window. She immediately alerted police, revealing Dikko’s identity as a former Nigerian minister. The news spread rapidly through Britain’s security apparatus and reached Scotland Yard’s anti-terrorist squad, the Home Office and even Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Charles Morrow, the Customs Officer Who Changed History

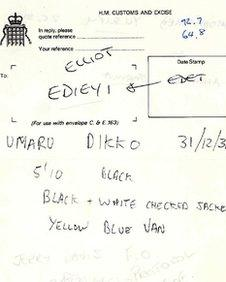

At Stansted Airport’s cargo terminal, around 4 PM, a van escorted by two black Mercedes-Benz cars with Nigerian diplomatic license plates arrived carrying two large crates. Also on duty that day was Charles David Morrow, a young customs officer whose sharp instincts would prove crucial.

“The day had gone fairly normally until about 3pm,” Morrow later recounted. “Then we had the handling agents come through and say that there was a cargo due to go on a Nigerian Airways 707, but the people delivering it didn’t want it manifested.”

Among those delivering the cargo were Major Yusufu and Okon Edet from the Nigerian High Commission. When Morrow questioned the contents, he was told it was just “documents and things.” But something didn’t feel right.

“Just then a colleague returned from the passenger terminal with some startling news,” Morrow continued. “There was an All Ports Bulletin from Scotland Yard saying that a Nigerian had been kidnapped and it was suspected he would be smuggled out of the country.”

Morrow’s training kicked in: “I just put two and two together. The classic customs approach is not to look for the goods, you look for the space. So I am looking out of the window and I can see the space which is these two crates, clearly big enough to get a man inside.”

The diplomatic protocol of the Vienna Convention protected such cargo from checks. However, the crates weren’t properly marked as “diplomatic bags” and lacked appropriate documentation. After consulting with the Foreign Office, Morrow received authorization to open them.

The Discovery

When Peter, the cargo manager, lifted the lid of the first crate, the Nigerian diplomat standing nearby “took off like a startled rabbit across the tarmac.” What they found inside defied belief.

“Peter looked into the crate and said: ‘There’s bodies inside!'” Morrow recalled.

In the first crate lay an unconscious Dikko, shirtless, with a heart monitor attached and an endotracheal tube in his throat to prevent choking. Beside him sat Dr. Shapiro, very much awake, surrounded by syringes and medical equipment to keep his patient alive but sedated during the journey.

The second crate contained Barak and Abithol, the kidnap team leaders, unrepentant to the end. As Morrow remembered: “They said Mr Dikko was the biggest crook in the world.”

Morrow’s emergency call captured the surreal nature of the discovery: “My name’s Morrow, from Customs at Stansted. We’ve got some bodies in a crate. Do you think you can send someone over?”

“Alive or Dead?” came the response.

“That’s a very good point. I don’t know,” Morrow replied.

“We’ll send an ambulance as well.”

The Aftermath: Diplomatic Warfare Ensues

The failed kidnapping triggered a diplomatic crisis between Britain and Nigeria. The British Parliament was outraged by what they saw as a flagrant violation of their sovereignty. MP George Robertson summed up the mood: “The message from this country and the House to the Nigerians or to anyone else who is aggrieved must be this: use courts, not crates.”

The Nigerian government initially denied involvement, with High Commissioner Major-General Haladu Anthony Hannaniya claiming it was the work of “some patriotic friends of Nigeria.” The involvement of the Nigerian government was admitted decades later by Hannaniya in his memoir.

General Buhari, stung by British criticism, released a statement accusing Britain of sitting “on the fence” while Nigeria faced “the test of economic survival.” Diplomatic relations collapsed completely, with both countries expelling each other’s diplomatic staff.

Justice and Aftermath

Four defendants including Barak, Shapiro, Abithol and Yusufu, faced trial at London’s Old Bailey. Despite claims they were merely mercenaries working for Nigerian businessmen, all were convicted and sentenced to prison terms ranging from 10 to 14 years. They served more than half their sentences before being deported to their home countries.

Umaru Dikko recovered fully from his 36-hour ordeal and remained in Britain for over a decade. In a twist worthy of a romantic thriller, he married Elizabeth Hayes, the secretary whose quick thinking had saved his life. He returned to Nigeria in 1995 under assurances from General Sani Abacha, who ironically, was one of the original coup plotters who had driven him into exile.

When Nigeria returned to democracy in 1999, Dikko petitioned a human rights panel investigating military-era abuses. His testimony revealed the lasting trauma: “Up to this day, the Nigerian government of that time or of any other time never admitted involvement in this international crime… My political career has been ruined and yet no guilt of any crime has been proved.”

Umaru Dikko lived quietly until his death from illness on July 1, 2014, in London, thirty years after the extraordinary events that made him one of the most famous fugitives in Cold War history. Buhari passed on more that a decade later.