Today, across cities and time zones, Nigerian Muslims abroad are celebrating Eid al-Adha, the Festival of Sacrifice. It’s a day rooted in the story of Prophet Ibrahim (or Abraham, peace be upon him), who, in a moment of absolute faith, prepared to offer his son Ismail (or Ishmael, peace be upon him) to God, only for mercy to arrive in the form of a ram. It marks the end of Hajj, the sacred pilgrimage and stands beside Eid al-Fitr as one of Islam’s two holiest days.

In Nigeria, Eid is a festival of sound, scent, and soul. They call it iléyá, a Yorùbá word that means ‘it’s time to go home.’ Cities empty out, villages fill up, and homes burst with the scent of grilled ram, the swish of new clothes, and the music of shared laughter.

But what if home is far away?

For many Nigerians living abroad, Eid doesn’t pause the city or close the stores. There are no public holidays, no street-wide feasts, no neighbours dropping off plates of Jollof rice or Amala. Still, somehow, Eid endures. It transforms, then travels and finds new form in unfamiliar places.

This is a story of Zainab, Abdul and Qudus, three Nigerian Muslims whose journeys reveal how faith is never left behind. It’s packed in suitcases, cooked into meals, prayed into silence and celebrated in small, defiant, beautiful ways.

Eid al-Adha: The Feast of Sacrifice

Eid al-Adha or the Feast of Sacrifice commemorates Prophet Abraham’s obedience to God’s command given to him in a dream vision to sacrifice his son, Ishmael. The Prophet had no children and had prayed to God for the gift of a son. God blessed him with a son, Ishmael.

In a dream, he saw himself sacrificing Ishmael. He proceeded to obey, but while he was in the act of sacrificing his son, God sent the Angel Gabriel with a huge ram. Angel Gabriel appeared to Abraham and informed him that his dream vision was fulfilled, and instructed him to sacrifice the ram as a substitute for his son. Eid al-Adha falls on the 10th day of Dhu al-Hijjah, the twelfth and final month in the Islamic calendar.

The day also marks the third and last day of Hajj or Pilgrimage, the fifth pillar of Islam. Hajj is an annual pilgrimage to Makkah and Madinah in Saudi Arabia that is obligatory for muslims who are physically and financially able to perform it once in their lifetime.

Muslims celebrate Eid al-Adha approximately 70 days after Eid al-Fitr, making it the second of the two major Islamic festivals. Eid Al-Fitr is celebrated to mark the end of Ramadan, the holy month of fasting.

How Nigerians Celebrate Eid at Home

Many communities refer to Eid al-Adha as Eid al-Kabir, Babbar Sallah in Hausa, or iléyá in Yorùbá. (iléyá means it is time to go home.)

Typically, for Eid al-Adha, Nigerians often travel to their ancestral villages to celebrate with their extended families. Families buy new clothes, scrub their homes spotless, and head to markets to choose a ram. For those who can’t afford one, neighbours often pool money together, a practice known as watanda.

The day begins with Salat al-Eid at specially designated prayer grounds. Men, women and children arrive in their finest fragranced attire. After the prayers and sermons, families perform the central ritual of Eid or the Qurbani sacrifice of rams, goats, cows or camels.

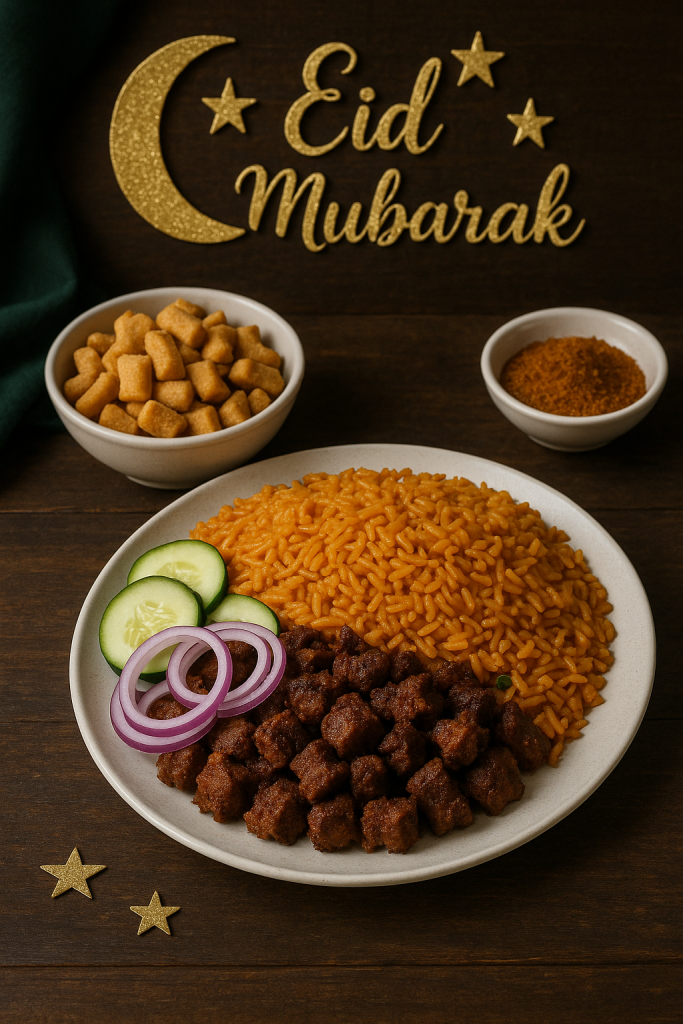

They divide the sacrificial meat into three parts: one for family, one for relatives and friends and one for the needy. In the north, they prepare Tuwo Shinkafa with the meat; in the southwest, it’s Amala and Ewedu. Elsewhere, Jollof rice takes centre stage. These hearty meals, rich with meat, travel from door to door and fill entire neighbourhoods with generosity.

The festival concludes with extensive visitations. Families travel between homes, children receive ‘Eidi‘ (gifts) and even non-Muslim neighbours often participate. In northern Nigeria, Eid blends with the vibrant Durbar festival and other local traditions. Emirs and chiefs often lead processions on adorned horses, and thrilling horse races.

In Ijebu Ode, on the third day after Eid, in the Ojude Oba Festival, the Yoruba equivalent of Durbar, age groups gather at the Awujale Pavilion. Ornately dressed horse riders parade before the Awujale while the age-grade groups compete in traditional attire and dancers perform cultural displays.

Eid Al-Fitr in 🇳🇬. This was shot during the Durbar festival in Kano state #kano #june #nigeria pic.twitter.com/Agyg2JWjlq

— Niyi (@theniyifagbemi) March 30, 2025

Zainab in Canada: Cooking Memories

Zainab moved to Canada to further her education. She left behind a childhood in Nigeria where, according to her, “Eid was a vibrant celebration filled with joy and connection.” Back home, her family would gather with friends and relatives, share meals, exchange gifts and engage in prayers. In her words, “the sense of community and togetherness during these occasions was truly special.”

Her first Eid in Canada brought unexpected challenges. “I didn’t bring any specific items from Nigeria in preparation,” she told us. Instead, she believed she could “adapt and embrace the new experience.” However, she encountered a jarring culture shock.

“Unlike in Nigeria, where Eid is widely celebrated with national holidays and where the atmosphere becomes festive as businesses close. Here, there were no public holidays set aside for Eid. Shops remained open, and many people continued their regular work schedules.“

Zainab

This difference left her feeling isolated, and she missed “the vibrant public festivities and communal joy that marked Eid back home.”

Despite the challenges, Zainab told us she has found community. Her most recent Eid celebration included “many Nigerian and non-Nigerian Muslims present. The atmosphere was filled with joy and we shared a variety of cultural foods, including Jollof rice, Suya, and Chin Chin.” The flavours brought back “cherished memories of home.”

For Nigerian Muslims abroad, Eid can feel like a quiet struggle not just to celebrate, but to preserve joy in unfamiliar soil. Zainab captures this shift poignantly: “I’ve quietly come to terms with the fact that I may forgo the tradition of slaughtering a ram.” Still, she holds fast to the heart of the celebration by giving alms, preparing food and opening her home to others.

When asked about what Eid means to her now, she offered something deeper than nostalgia:

“Celebrating Eid far from home has taught me resilience and adaptability,” Zainab reflects. “I’ve learned that the essence of our traditions can transcend geographical boundaries, and that joy can be created in new ways.” Her story mirrors that of many Nigerian Muslims abroad during Eid. Even in distant lands, traditions can be reimagined, not lost.

Abdul in New York: Naming What’s Lost

From Nigeria to New York

Abdul completed his studies in Chicago in 2015. He lived in Nigeria between 2015 and 2017, then moved to New York.

He remembers Eid in Nigeria as energetic and youthful. Friends in corporate jobs would gather and celebrate. In his words, “it was much more fun compared to university days [in Chicago]. Everyone was younger, everyone was almost done.”

In contrast, his first Eid in New York felt empty. He attended prayers at the Islamic Centre at NYU, dressed in full regalia, but everyone dispersed for work immediately after.

“Monday again, everyone is at work,” he says. He also couldn’t fly to Nigeria for Eid with a flight ticket costing up to $2,000, a price many cannot afford. Other groups, he notes, like the Igbos, manage stronger connections through frequent visits.

A Shift in Faith and Visibility

While New York and parts of New Jersey now recognise Eid as a school holiday, American society at large remains unaware. “The only time you know that something’s happening is if there’s a program,” he explains. “After that, nothing. There’s no sales, you know how in Nigeria they have sales… There’s nothing like that at Walmart or Walgreens, everything’s just normal.”

Naming What We’ve Lost

Abdul worries about what may fade. “Our kids won’t know iléyá the way we did: the takbirs, the meat, the joy. I try to show them glimpses. But it feels like offering a translated memory.”

This longing for home isn’t rare. Across the diaspora, others feel it too. For some, like African Americans moving to Kenya, it inspires cultural rebirth, as explored in this piece.

He notes that places like Texas and Chicago with larger Muslim communities, offer more vibrant celebrations. However, his experience is no match for what it is at home “We accept the mediocrity of the Muslim experience outside Nigeria. Being a Muslim in Nigeria is so radically different.”

Still, he holds hope. “Maybe the next generation will build something better. But first, we must name what we’ve lost.”

Qudus: From France to Florida

A Joyful Start in Nigeria

Qudus moved to France in 2014, then to the U.S. in 2019. His childhood in Nigeria gave him full Eid experiences: ice cream, sallah rams, new money notes, and family closeness.

Faith Under Pressure in France

France introduced a stark shift. The secular culture brought restrictions on religious expression. “They actually released the law that was against hijab… you cannot wear a hijab in public spaces because they claim that they are a secular country.”

The impact was deeply personal. His girlfriend, now wife, “was not even wearing any hijab, she was just wearing a cap, you know, like a normal cap to cover her hair and they at some point, they have to stop her from attending school.” He remembers the day she called him, crying because she felt persecuted.

This experience made Qudus forge a private connection with Islam. “I learned to be an individual Muslim, to seek my own connection and relationship with Allah, which is not entirely connected to community.” Without family or an established Muslim community, he relied on YouTube videos and scholars like Zakir Naik for spiritual guidance.

Halal, Diet, and Exhaustion

Even dietary practices became politicized. “The notion of halal became a political issue,” he explains. Rather than constantly explaining his dietary restrictions, he adopted what he calls being a “partial vegetarian,” telling people he simply didn’t eat meat to avoid having to explain himself.

Finding Solitude and Clarity in the U.S.

In Gainesville, Florida, he found diversity: professors and researchers from Egypt, Brazil, Greece, Algeria, Pakistan and France. But he still preferred solitude. “I don’t do communities,” he says.

Reimagining Eid: From Isolation to Innovation

A Global Migration, A Local Gap

According to Pew Research, Muslims make up 29% of global migrants, or over 80 million people. Yet in North America and Europe, Eid is still underrepresented in public life.

But that gap is not a dead end. It is an invitation.

What if tradition was not only preserved, but reimagined?

Taking Cues From Others

Diaspora Christian groups have quietly built powerful cultural economies. From Ugandan Christmas fairs in UK churches to Caribbean gospel brunches in New York, many began small. A rented hall. A shared meal. A collection plate.

Some have grown into million-dollar businesses, real estate collectives, even schools.

There is no reason Muslim communities abroad cannot do the same.

Building Eid, One Small Act at a Time

Rather than nostalgia, Eid abroad can become a movement. Here are practical ways Nigerian Muslims in the diaspora are creating new traditions:

1. Host a Local Eid Potluck

Start with five families. A borrowed community hall. Bring food. Share stories. Pray together. Like church picnics, but this time, with Suya and Jollof.

2. Start a Micro Eid Bazaar

Invite local vendors, modest fashion, halal skincare and children’s books. Charge a symbolic fee. Use proceeds to fund community projects. For example, London’s Eid in the Square now draws 25,000+ and supports dozens of Muslim-run brands.

3. Curate Eid Gift Boxes

Sell curated gift kits online: Suya rubs, chin chin, prayer mats, storybooks. Use Etsy, WhatsApp, or Shopify. Take Eid Party UK which began in a living room and now dominates halal holiday e-commerce.

It’s Not That Hard, It’s Already Happening

- Toronto’s MAC Eid Festival started with community prayers and now fills a convention center with food stalls and families.

- Atlanta’s Eid Fest transformed a park meet-up into a full-blown theme park experience.

- Faith and Fashion events in London mix runway with Ramadan, community with commerce.

These began on small side-hustle style budgets.

Faith. Food. Future.

If Prophet Ibrahim (peace be upon him) walked into uncertainty with faith, perhaps this moment calls for similar resolve. You can start with:

- A grill in the backyard

- A playlist of takbirs

- A few friends and a table

That’s it.

Eid abroad isn’t less. It’s just beginning.

For anyone reading this while juggling work meetings and stirring Jollof on the stove, this might be the sign:

There is no need to wait for someone else to build it. Start it.

Eid Mubarak. Let the building begin.