Nigeria’s railway system is one of too many tragic tales of promise unfulfilled, dreams deferred and opportunities squandered that litter Nigeria’s history. What began as an ambitious colonial infrastructure project has since devolved into a permanent symbol of institutional failure, corruption and mismanagement that continues to plague Nigeria over a century later.

Built By the Empire

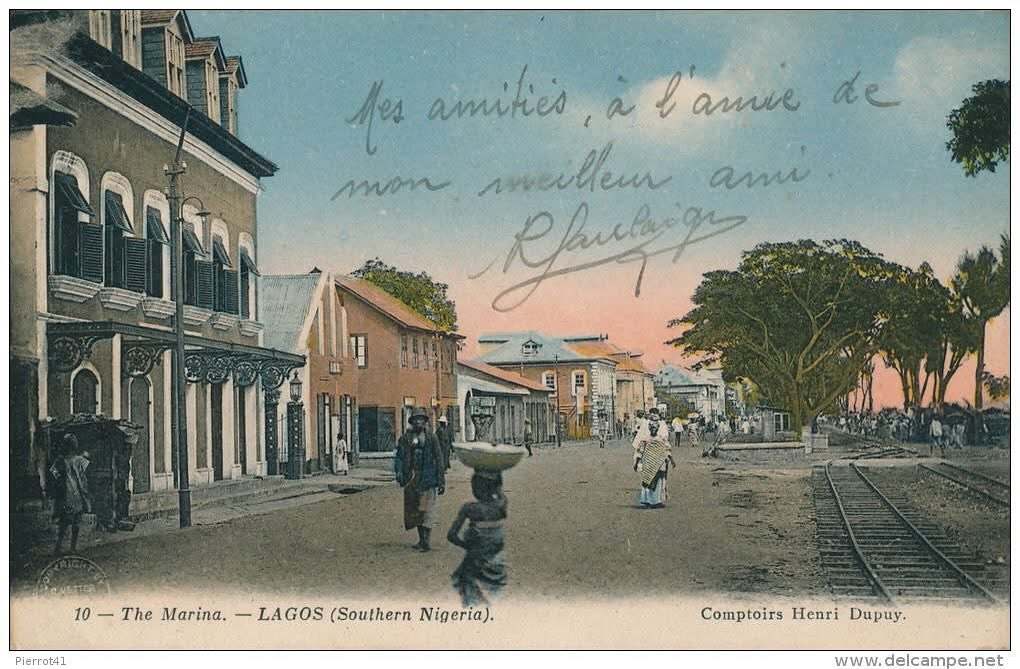

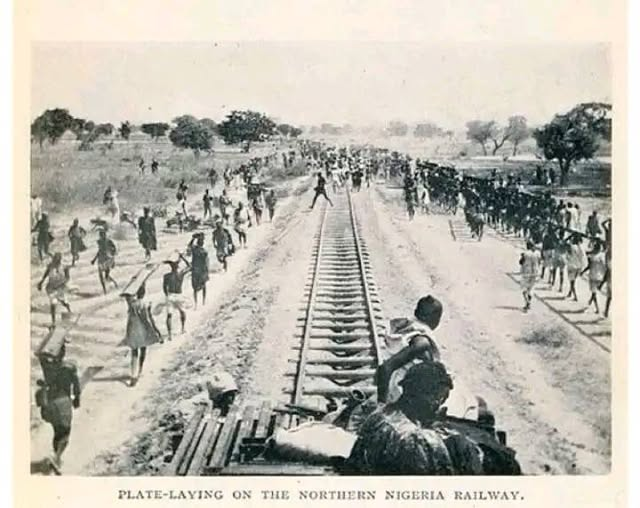

The story of Nigeria’s railway begins in the dying years of the 19th century when British colonial authorities embarked on an ambitious railway construction program. The development of railways in Nigeria started from Lagos Colony to Ibadan in March 1896, with the Lagos Government Railway beginning operations in March 1901. The initial 32-kilometre line of narrow-gauge track originated from Iddo (Lagos) and extended to Ota (Ogun), before authorities expanded it to Ibadan, bringing the total length to 193 kilometres.

The colonial railway network expanded steadily through the early 20th century. Railway construction experienced continual extension: Ibadan to Jebba (295km) between 1901-1910; Kano to Baro (562km) from 1907-1911; Jebba to Minna (252km) during 1909-1915; Port-Harcourt to Enugu (243km) from 1914-1916; and Kafanchan- to Jos (179km) between 1922–1927.

After discovering coal at Udi, colonial authorities constructed the Eastern Railway to Port Harcourt between 1913 and 1916, and later extended it to Kaduna in 1927 to connect it with the Lagos–Kano Railway.

Supporting Nigeria’s Agriculture

During this golden era, the single-track narrow-gauge rail network ran diagonally across the country and was well able to haul all the agricultural products grown in the far north to the seaports at Lagos and Port Harcourt. The contribution of groundnuts from northern Nigeria, palm oil from eastern Nigeria and cocoa from western Nigeria to the flourishing Nigerian economy at the time serves as reminders of the good old railway era.

The railway system played a pivotal role in increasing commercial activities in towns along the rail routes. It boosted inter-ethnic marriages, facilitated cultural exchange and created mega towns referred to as railway towns such as Lagos, Umuahia, Zaria, Kano, Kafanchan, Jos, Enugu, Aba and Port Harcourt.

By 1964, at the height of its performance, the Nigerian Railway Corporation carried 11,288,000 passengers and 2,960,000 tonnes of freight annually. The system had reached its zenith with a total rail route network of 3,505 kilometres by the completion of the Bauchi-Maiduguri line in 1964.

The Descent Begins Immediately After Independence

However, ominous signs of decline emerged almost immediately after independence. A steady process of decay crept into operations in the late 1970s, that became worse with the systemic deterioration of the corporation’s entire infrastructure and manpower. Statistics reveal the dramatic fall: by 1974, just ten years after the peak, passenger numbers had plummeted to 4,342,000 and freight tonnage dropped to 1,098,000.

Former President of the Nigeria Union of Railway Workers, Ado Maigoro, recalls the contrast: “In those good old days of the railway, we had trains moving on a daily basis from Lagos to Kano; Kano to Lagos: Port Harcourt to Kano; Kano to Port Harcourt and Jos to Port Harcourt; while Lagos-Maiduguri train ran four times weekly, apart from the mass transit in Lagos and other towns.”

The fundamental problem was strategic neglect. However, successive governments abandoned further railway development and prioritized road transport. They expanded the road network without considering adverse effects such as road traffic accidents, environmental pollution, congestion and inadequate parking. Some administrations even built highways parallel to existing railway lines, thereby turning road and rail systems into competitors rather than complementary services.

According to Chinedu Arizona-Ogwu, technical problems compounded the institutional failures: tight curves, steep gradients, rail buckling with associated track/speed limits, poor communications, government interference with management structure, lack of freedom to set tariffs, under-funding, falling rolling stock levels, plummeting traffic levels, inflexible bureaucracy, volatile labour unions, irregular staff training, worn-out infrastructure and lack of maintenance killed the rail transport system.

For 31 years, from 1927 to 1958, there was virtually no railway development. This period of stagnation would prove prophetic of things to come.

Failed Foreign Interventions

Recognizing the crisis, successive governments turned to foreign expertise to help revitalize Nigeria’s railway system. The results were mixed and often disastrous. In the late 1970s, the military regime headed by Olusegun Obasanjo invited Rail India Technical and Economic Services to manage the NRC. The Indian experts found only 20 functional locomotive engines in the system. By the time they left in the early 1980s, this number had increased to 173.

“The Indians did not perform any magic,” Maigoro explains. “They succeeded only because they received adequate funds from the government to put things right. What the railway needs even now is adequate funding to replace and repair obsolete rolling stock.”

The Indians neither trained Nigerians adequately nor improved operational services sustainably. The project’s unsuccessful completion and resultant failure of the railway to work proficiently highlighted the need for more comprehensive reform.

Romanian experts followed with a project for the supply of Rolling Stock and Workshop equipment between 1986-1996. But this too remained inconclusive, with supplied facilities reportedly gathering dust at NRC workshops, uninstalled due to what officials describe as “manual blunders.”

The Chinese Debacle

The most spectacular failure came with Chinese involvement. In 1995, General Sani Abacha’s administration awarded a whopping $528 million, about ₦45 billion, contract to China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) for railway rehabilitation and acquisition of rolling stock. Of the 50 locomotives supplied by CCECC in 1995, only 10 were currently serviceable, with others grounded due to a lack of spare parts.

A Chinese firm delivered substandard locomotives, wagons and coaches that failed to meet usability standards. Spare parts for the narrow-gauge locomotives and coaches became nearly impossible to source. The reason was that the original manufacturers in Europe, the Americas and Asia had already discontinued their production. Despite this poor performance, the Nigerian government re-awarded the same Chinese firm another $8.3 billion contract to rehabilitate the rail system. In 2006, Beijing and Abuja negotiated a deal under which China would offer a $1 billion concessional loan, while Nigeria would provide matching funds.

The pattern repeated itself during the Obasanjo administration. On November 28, 2006, Obasanjo inaugurated construction of a new Lagos-Kano standard gauge line spanning 1,315km. The government awarded the contract to the China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC). The CCECC received an initial payment of $250 million before the Yar’Adua administration later suspended the project.

Giving reasons for the project’s suspension, former Minister of Transport Ibrahim Bio explained: “The Chinese government was able to stimulate the interest of the Federal Government by proposing to give a soft loan of $2.5bn and that attracted the government. When we went in for it, they retracted and said they only had $500m and that we should source for the balance from Chinese banks at their prevailing interest rates.”

The Jonathan Era: Massive Investment, Minimal Returns

The Goodluck Jonathan administration gave considerable attention to Nigeria’s railway system. The administration made it a cardinal point of its Transformation Agenda. The sector received funds in essence of ₦1 trillion. In 2013, the administration promised to invest N1.6 trillion in the railway over two years, with 15 different railway projects penciled for completion by 2015.

The federal government purchased a total of 25 new locomotives from General Electric Transportation South America at a cost of N114 billion. The new locomotives were delivered between February and October 2010. However, a recent survey shows that fewer than 30 engines are still standing, according to the Secretary General of the Nigeria Union of Railway Workers, Segun Esan.

The administration also procured 366 coaches and wagons. Also purchased were two sets of diesel multiple units with a capacity for 640 passengers, and six modern air-conditioned coaches with a seating capacity of 68 passengers each. Despite these massive investments, the railway remained largely dysfunctional.

Following Jonathan’s tenure, Nigeria commissioned several major rail lines. The government inaugurated the Abuja–Kaduna Standard-Gauge in July 2016 and the Lagos–Ibadan line in June 2021.

More Modern Disasters

Despite these efforts, new rail lines have not remained free of problems. In April 2025, the Nigerian Railway Corporation suspended Warri–Itakpe operations after a major engine failure stranded passengers in a remote forest in Kogi State. With no access to mobile network coverage or security presence, the passengers trekked through dense bushland that was described by one passenger as an “evil forest” in search of safety.

Activist Kola Edokpayi, one of the affected passengers, shared a disturbing account: “We became apprehensive. We were stranded in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by forest and with no idea how long the repair would take. So, we decided to start trekking.” He described the ordeal as an “endurance trek” that lasted over three hours.

The incident prompted Edokpayi to warn: “Airlines cancel flights without notice, roads are unsafe due to kidnappers and poor conditions, and now trains are breaking down in forests. May God continue to help us in this country.”

The Security Crisis

Insecurity has also dealt a devastating blow to the already struggling system. According to National Bureau of Statistics data, passenger movement declined by 125.6 percent in the second quarter of 2022, with only 422,393 passengers traveling by train compared to 953,099 in the first quarter. This decline followed the March 28, 2022 Kaduna train kidnapping incident.

“It is foolishness to continue to build infrastructure when the security of lives is in jeopardy,” said Samuel Odewumi, a professor and former dean at Lagos State University School of Transport and Logistics.

Revenue from passengers decreased by 76.2 percent, from ₦2.1 billion in Q1 2022 to ₦500 million in Q2. No fewer than 3,420 people were abducted across Nigeria between July 2021 and June 2022, with 564 others killed in violence associated with abductions.

Even when trains do run, passenger experiences remain poor. Alimah Omodele, traveling to Ilorin, told Punch: “My mother-in-law told me it would be fun and promised to pick me up at the railway station in Ilorin when we arrive. But I’ve not seen any fun except the AC.”

Navy employee Yakubu Abdullahi, who paid ₦6,050 for a first-class sleeper coach, complained: “What I saw on the NRC website fascinated me. It gave an indication that the train is next to the airplane experience. But I’m seeing a different thing now. The AC, the toilet, the bedding and the whole place looks old-fashioned and unattractive. It is not worth my ₦6,050.”

Reports have also revealed widespread theft of rail clips. Between 2022 and 2023, suspected vandals stole over 150,000 clips along railway tracks across the country, according to the Nigerian Railway Corporation (NRC). NRC officials further noted that each effort to replace the stolen clips is often followed by renewed theft, which creates a cycle of relentless sabotage.

The Corruption Factor

Analysts have consistently identified corruption at the highest levels of government as the central problem undermining Nigeria’s railway system. The President of the African Railway Workers’ Union, Raphael Okoro, blames the Federal Ministry of Transport for preparing contract terms and executing projects without input from relevant NRC experts.

“All railway contracts are initiated and executed by the Ministry of Transport. For instance, you go to purchase railway locomotives and leave out NRC engineers. Lack of proper monitoring has been largely responsible for the failure of many railway projects,” he says.

The reasons for the failure of both Indian and Chinese rail reconstruction contracts have been attributed to what observers call “the Nigerian factor of corruption at the apex of government.”

Any Hope Left? Analysts and Experts Think So

Despite decades of failure, analysts believe that Nigeria’s railway system can be resuscitated with the right approach. Dr. Ayo Teriba, a renowned economist, advocates for ending government monopoly: “The government should do to its rail transport sector what it has beneficially done to its telecommunications sector, and has recently done to its power sector; namely, end government monopoly, carve out the country into zones and allow private firms to bid for the rights to build and/or operate rail lines under the oversight of a new regulatory body.”

The World Bank emphasizes good governance: “Good governance for railways is governance that drives the railway to be market-oriented, efficient, and financially sustainable and to manage the railway assets for the long term.”

Nigeria’s Railway workers’ union leaders suggest involving experts in planning. Secretary-General of the NUR, Segun Esan urged the government to “constitute a high-powered team made up of respected railway experts, trusted opinion leaders, human right lawyers and workers’ leaders that will be saddled with the task of assessing railway project proposals and monitor the execution of the job.”

Some experts recommend regional approaches. Raphael Okoro advises state governors across the six regions to pool resources together for establishing regional railways using Public Private Partnership models. The fundamental challenge to this remains the Railway Act of 1955, which confers absolute monopoly rights on the government to run railways and forbids private sector participation. A bill seeking amendment has reportedly undergone second reading at the Senate after years of delay.

It should go without saying:

Nigeria’s railway collapse embodies the broader challenges of governance, corruption and institutional weakness that have plagued the nation since independence. Without addressing these fundamental issues, even the most ambitious rehabilitation efforts will continue to derail, leaving millions of Nigerians stranded on the platform of unfulfilled promises. The resurrection of Nigeria’s railway system ultimately, requires not just new tracks and trains, but a complete overhaul of the mindset and systems that led to its spectacular collapse, which are now impeding its revival.