Nigeria’s textile industry is as famous as Rashidi Yekini. He rose to fame while working for United Nigeria Textiles Ltd and playing for the company’s football team.

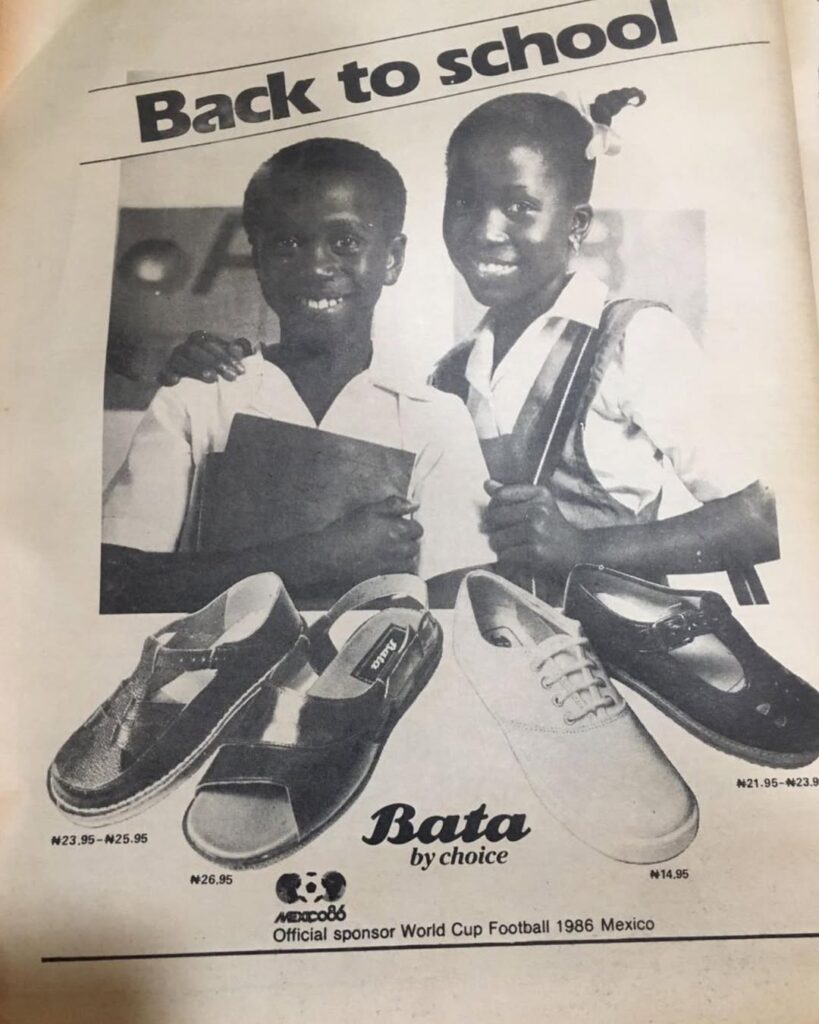

Yes, once upon a time, “Made in Nigeria” was a mark of quality. They were given out as wedding gifts and heirlooms. They dominated West African markets, with UNTL, Arewa Textiles and Finetex regarded as the gold standard.

Yet, this industry that was once a critical pillar of Nigeria’s economy has long collapsed, with the interventions of successive governments failing to revive it.

The Rise of Nigeria’s Textile Industry

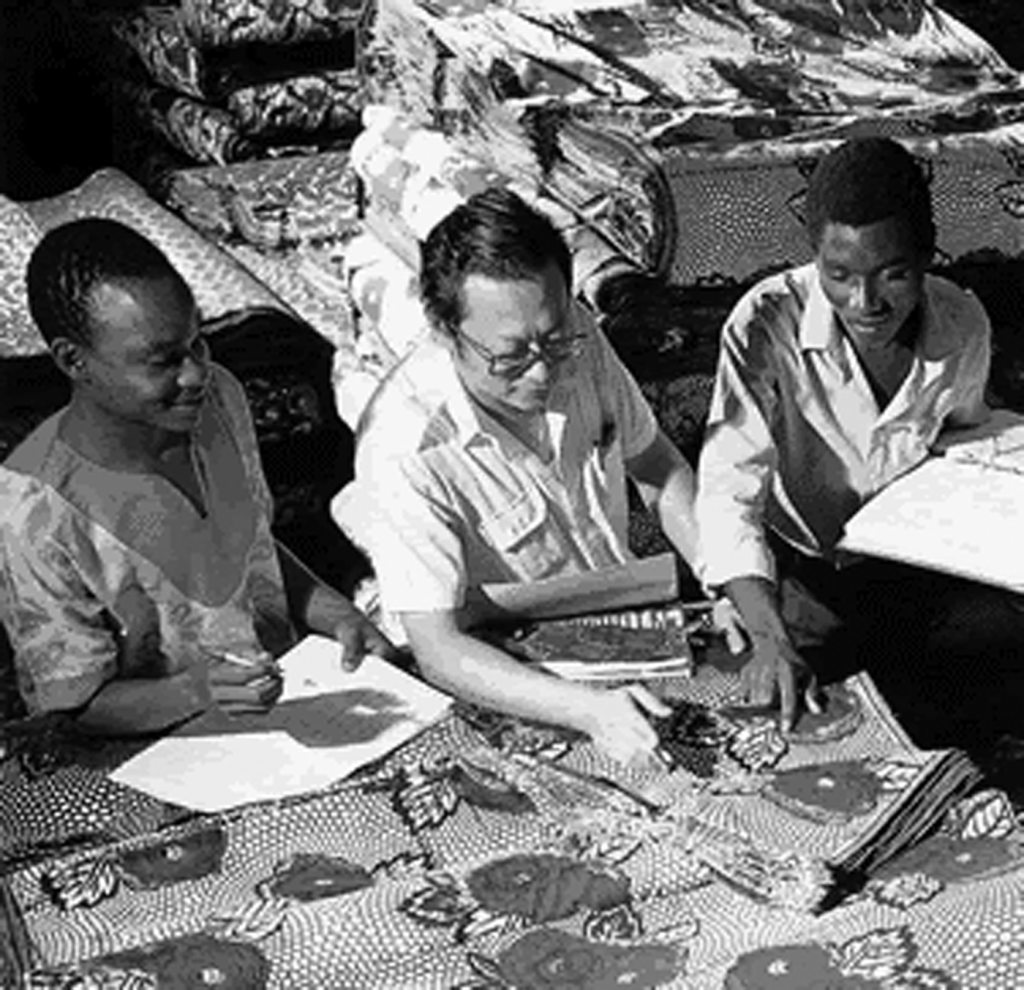

Nigeria’s journey in textiles began shortly before independence, when the United Nigerian Textiles Limited (UNTL) was established in 1956. UNTL was established in partnership with the Hong Kong-based company, Cha Group, which was incorporated only a year earlier. The goal was to process the cotton being produced at the time, in the northern part of the country. Both Chinese and Nigerian workers worked at UNTL’s mills in Kaduna.

UNTL was followed by Arewa Textiles, which was established in 1965. And as the newly independent nation sought to quickly industrialize, other companies like Afprint, Enpee, Asaba Textiles, Aswani Textiles and Five Star squeezed into the growing industry.

According to estimates by the Textile Association of Nigeria, between 1970 and 1987, the Nigerian textile industry flourished beyond all expectations. The demand for products exceeded supply by an astonishing 91%. The industry employed over 350,000 workers directly and created millions of indirect jobs and ranking second only to the Nigerian government as the country’s largest employer of labour. By the mid-1980s, Nigeria was home to 175 textile mills. The mills were concentrated in Aba, Asaba, Funtua, Gusau, Kaduna, Kano, Port Harcourt and Lagos. Kaduna hosted three of the biggest and largest mills, earning itself the nickname, Textile City.

By 1987, Nigeria’s textile industry had grown to become the third largest in Africa, after Egypt and South Africa, with factories operating over 50% of their utilization capacity. According to the United Nations University (UNU) in 1987, there were 37 textile firms in the country, operating 716,000 spindles and 17,541 looms. In this period, the industry recorded an annual growth of 67%, and by 1991, it employed about 25% of all Nigerians working in the manufacturing sector.

During this period, the industry directly or indirectly supported more than 17.2 million Nigerians. Cotton farmers across the northern states supplied raw materials and created a valuable agricultural-industrial symbiosis that supported livelihoods across the country. The cornerstone of Nigeria’s manufacturing sector, the industry’s contribution to Nigeria’s GDP was massive: an estimated $9 billion in annual revenues.

Then Came the Collapse

The collapse of Nigeria’s textile industry didn’t happen overnight. It was instead a slow, painful descent that began in the mid-1980s and accelerated through the 1990s and 2000s. A lot of factors contributed.

Currency Devaluation and Structural Adjustment

The beginning of the end of the textile industry can be traced to the economic reforms of the 1980s. In 1986, Nigeria implemented a Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) under pressure from international financial institutions. The naira was floated, resulting in a steep devaluation, from around N3 to the US dollar to N30 by 1985. Textile manufacturers who had taken foreign loans to expand their operations could not repay them because of upward revisions in foreign exchange rates.

The WTO Trap

In 1995, Nigeria’s became a member of the World Trade Organization. This ended the chances of reviving the textile industry. The timing was catastrophic, it came just as the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA), which had protected developing countries through textile quotas, was being phased out by 2005.

Under WTO rules, Nigeria was forced to dismantle protections for its local textile manufacturers and expose them to unrestricted global competition. Instead, Nigeria opened its markets completely at a time its textile sector was still vulnerable.

This led to the Chines invasion.

The Chinese Invasion

While currency issues were significant, the most devastating blow to the industry came from trade liberalization policies of the 90s. Opening Nigeria’s markets to global competition under WTO rules exposed local manufacturers to cheaper imports, particularly from China. China’s textile industry benefits from an integrated supply chain that allows it to produce all necessary inputs domestically. This means they can produce at a cheaper price. And Chinese manufacturers flooded Nigerian markets with cheaper alternatives.

Also, the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), meant to boost African textile exports to the US, became meaningless as Chinese competition proved insurmountable. Nigerian textile companies found themselves fighting a losing battle on two fronts: defending their domestic market from Chinese imports while failing to capture export opportunities that China dominated.

Moreover, these Chinese manufacturers began copying Nigerian designs and producing them at lower costs with polyester fakes instead of cotton. They even sewed the highly respected ‘Made in Nigeria’ badge onto them.

The Smuggling Economy

The import ban on textiles implemented by President Obasanjo in 2002 did little to stem the tide. Instead, it created a thriving smuggling economy. The World Bank estimated that textiles smuggled into Nigeria through Benin were worth $2.2 billion annually, compared to local Nigerian production that shrivelled to just $40 million.

A significant figure in this smuggling economy was businessman Dahiru Mangal, who allegedly facilitated the import of Chinese textiles through neighbouring countries. Operating from Katsina, Mangal was estimated to be bringing about 100 40-foot shipping containers across the frontier each month in 2008. As described by journalist Tom Burgis in his book The Looting Machine, Mangal “plies the hidden byways of the globalised economy,” acting as “the conduit between manufacturer and distributor, managing a shadow economy that includes the border authorities and his political allies.”

Read: Did Dahiru Mangal Kill The Nigerian Textile Industry?

Infrastructure Decay and Power Crisis

There was also a lack of reliable electricity. This played a key role in the industry’s decline as it did in many others. Textile manufacturing is energy-intensive and chronic electricity shortages forced manufacturers to rely on expensive diesel generators. This significantly increased production costs. The unreliable power supply made it nearly impossible for Nigerian manufacturers to compete with countries like China, where electricity is stable and virtually inexpensive.

The Human Cost of the Collapse of Nigeria’s Textile Industry

By the mid-1990s, the decline was evident. Between 1994 and 2005, about 64% of Nigeria’s registered textile companies had disappeared, with the number falling from 125 to 45. Employment plummeted from 137,000 in 1996 to 24,000 in 2008, and by 2022, fewer than 20,000 jobs remained in the industry.

The collapse rippled throughout Nigeria’s economy. About half of a million farmers who used to grow cotton to supply textile mills no longer do so. Each textile employee typically supported half a dozen relatives, meaning millions of Nigerians have been affected. In Kaduna, once-vibrant industrial zones became ghost towns. The football club where Rashidi Yekini once played disappeared along with the factory that sponsored it. The decline of the textile industry coincided with rising unemployment and increasing social unrest, particularly in northern Nigeria.

Failed Revival Attempts

Successive Nigerian governments have attempted to revive the textile industry, with limited success. President Obasanjo launched a ₦70 billion Textile Development Fund just before leaving office in 2007. President Yar’Adua increased this to ₦100 billion and appealed to Nigerians to buy local textiles. The Jonathan administration continued with the fund, disbursing ₦60 billion by the end of his tenure.

More recently, the government claimed to have secured a $3.5 billion investment for the sector. Vice President Kashim Shettima announced collaboration with the International Cotton Advisory Committee (ICAC) to revive the sector and create 1.4 million jobs annually, though Nigeria had previously lost its ICAC membership due to unpaid dues.

Can Nigeria’s Textile Industry Rise Again?

The revival of Nigeria’s textile industry requires addressing multiple challenges simultaneously. First, there has to be cheap and sustainable electricity. Nothing else can work without this. Also needed is a new import-export policy that will favour our textile manufacturers. This, however, creates the risk of opening smuggling corridors and enriching those close to power. Regardless, it can help if supported by a strong political will. Other necessary steps include developing the local cotton value chain and modernizing production technologies.

The potential benefits are substantial. A revived textile industry could once again employ hundreds of thousands of Nigerians, support cotton farmers, generate tax revenue and reduce the $30 billion that is currently spent on importing textile materials.

Our textile industry is one of many nostalgic reminders of our past industrial glory. Regardless, the machines that once provided livelihood for generations of Nigerians stand silent, but with the right policies and investment, their hum might once again fill factory floors across the nation.