In August 1973, Paul McCartney, former Beatle and leader of Wings, made a decision that would have seemed reckless to any sensible rock star: record his next album in Lagos, Nigeria. Not the familiar confines of Abbey Road, not the cutting-edge studios of Los Angeles or New York, but a ramshackle EMI facility in West Africa that he’d never seen, in a country under military rule.

What followed over the next month would become the stuff of rock legend: a tale of armed robbery, health scares, cultural confrontations and technical nightmares that somehow produced McCartney’s finest post-Beatles work. Yet the man himself bristles at the romantic notion that suffering breeds great art. “Anything for an easy life with me,” McCartney insisted in 2010, dismissing the idea that Lagos’s hardships enhanced his creativity.

Yet, the paradox remains: he never made a greater album after Lagos.

The Restless Vision

By 1973, Paul McCartney was a man in creative flux. His first three Wings albums had achieved commercial success. Live and Let Die dominated the charts and Red Rose Speedway proved his commercial instincts remained sharp. But critics remained skeptical. They saw him as lightweight compared to John Lennon’s raw political edge or George Harrison’s spiritual gravitas. The shadow of the Beatles loomed large, and McCartney felt the weight of expectations to prove himself worthy of his own legacy.

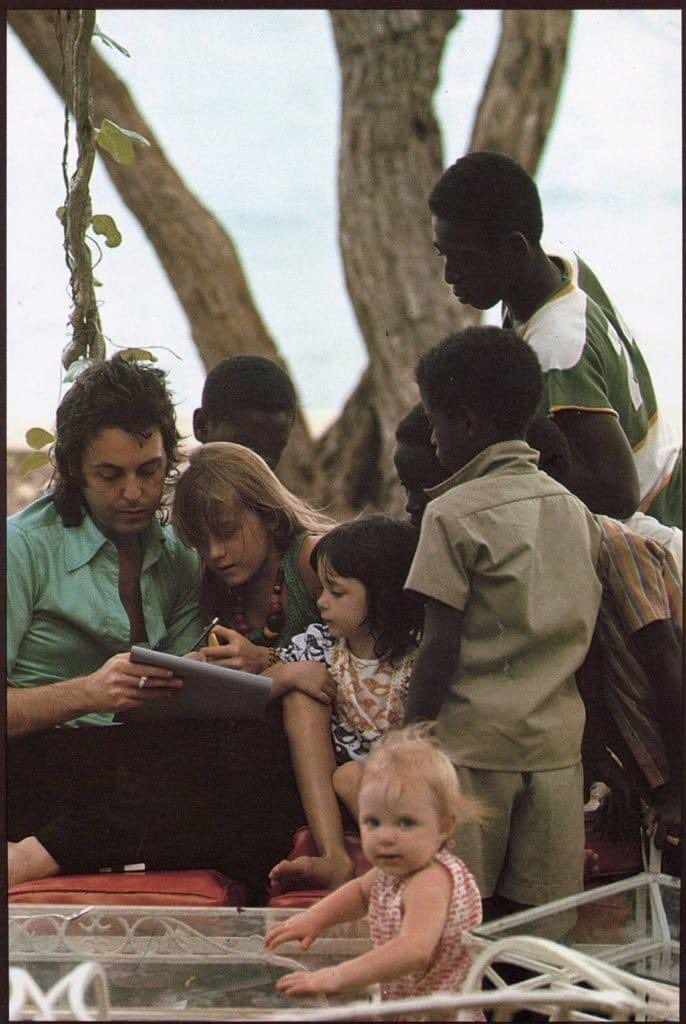

The Lagos inspiration came from a simple request to EMI for a list of their international studios. Something about the African location sparked his imagination. McCartney later recalled thinking “Africa… rhythms… yeah” when considering the possibilities. He envisioned absorbing the continent’s musical energy, perhaps even collaborating with local musicians and creating something that transcended his British pop sensibilities.

Speaking at the time his gave his explanation for why he chose to come to Lagos thus: “I thought my visit would, if anything, help them, because it would draw attention to Lagos and people would say, ‘Oh, by the way, what’s the music down there like?’ and I’d say it was unbelievable. It is unbelievable … it’s incredible music down there. I think it will come to the fore.”

The romantic vision began crumbling before they even departed. Lead guitarist Henry McCullough quit in Scotland just weeks before the planned departure, frustrated by McCartney’s tight artistic control. Drummer Denny Seiwell followed suit the night before their August 8th departure and left only the core trio of Paul, Linda and guitarist Denny Laine to make the journey, accompanied by former Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick and two roadies.

Welcome to Lagos!

The band and their entourage arrived in Lagos on August 30, 1973 and wouldn’t return to London until late September 22nd. What they found was a country bearing little resemblance to McCartney’s tropical fantasies. Nigeria in 1973 was under military rule, with General Yakubu Gowon’s regime casting a heavy shadow over daily life. Corruption was endemic, infrastructure was poor and the rainy season’s tail end brought oppressive heat and humidity that left the British visitors wilting.

EMI’s studio, located on Wharf Road in the suburb of Apapa, was ramshackle and under-equipped. The control desk was faulty and there was only one tape machine, a Studer 8-track. While this was high-tech compared to the 4-track that Sergeant Pepper’s had been recorded on in 1967, by 1973 it was primitive by industry standards. The studio lacked vocal booths, proper acoustics and reliable air conditioning, making it a far cry from the state-of-the-art facilities McCartney was accustomed to.

The band established a routine despite the challenges. They rented houses near the airport in Ikeja, an hour’s drive from the studio. Paul temporarily joined a country club where he’d spend mornings before the afternoon trek to Apapa. Recording sessions stretched into the late evening and sometimes early morning hours, with McCartney forced to assume multiple roles. He played drums and led guitar to compensate for the departed band members.

When the Unthinkable Happened

The Lagos experience took a dangerous turn during what should have been a simple evening walk. McCartney and Linda, ignoring local advice about venturing out after dark, found themselves confronted by a group of men in a car who repeatedly offered them a ride. When McCartney lost patience and physically confronted one of the men, and bundled him back into the vehicle, the situation escalated quickly.

The rest of the six-man gang emerged from the car with one of them brandishing a knife. “The penny dropped,” McCartney recalled years later. The couple surrendered their valuables, including cameras, cash, and most devastatingly, a bag containing demo tapes and handwritten lyrics for the album they were there to record. Linda’s desperate plea that her husband was “a musician” fell on deaf ears. The thieves, oblivious to the priceless nature of their musical loot, likely discarded the tapes as worthless.

The robbery’s psychological impact was profound. It stripped away any remaining illusions about their African adventure and replaced romantic notions about the Lagos sun and beach with stark awareness of their vulnerability. The loss of the demos meant starting over and rebuilding songs from memory and instinct rather than careful pre-planning.

Facing off With Fela

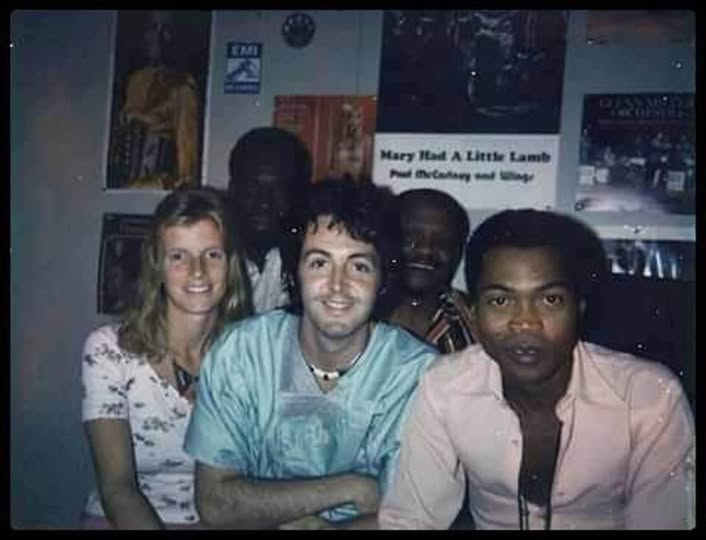

The challenges extended beyond crime and poor facilities. Paul McCartney found himself confronting one of Nigeria’s most formidable cultural figures: Fela Kuti, the pioneering Afrobeat musician and fierce political activist. Kuti publicly accused Paul McCartney of coming to Africa to exploit indigenous music. He viewed the British star’s presence as another form of cultural colonialism.

Speaking at the time, McCartney said, “We were gonna use African musicians, but when we were told we were about to pinch the music we thought, ‘Well, up to you, we’ll do it ourselves.’ Fela thought we were stealing black African music, the Lagos sound. So I had to say, “Do us a favour, Fela, we do OK. We’re all right as it is. We sell a couple of records here and there.”

The tension was both personal and symbolic. The former colonial power’s musical ambassador facing off against Africa’s most uncompromising artistic voice. McCartney eventually invited Fela Kuti to the studio to hear what Wings was actually recording as a way of proving their music contained no direct African influences. The confrontation eventually cooled, but it added another layer of pressure to an already stressful situation.

Health scares compounded the difficulties. In the middle of a session, Paul collapsed from a bronchial spasm caused by too much smoking. Engineer Geoff Emerick later described the terrifying scene: “Within seconds, he turned as white as a sheet, explaining to us in a croaking voice that he couldn’t catch his breath.” The Lagos heat made the situation worse, and McCartney fainted completely. Linda’s hysterical screams, convinced her husband was dying, echoed through the ramshackle studio. The incident forced McCartney to confront his smoking habit and would quit soon after returning to England.

The Paradox of Paul McCartney’s Lagos Experience

Yet something remarkable was happening amid the chaos. Stripped of his usual resources and collaborators, McCartney was forced to dig deeper into his musical instincts. The primitive 8-track setup meant no endless overdubs or studio indulgence. Every note now had to justify its existence. Linda, still learning keyboards, contributed simple but effective parts that added unexpected texture. The reduced band line-up created space for Paul McCartney’s multiple instrumental personalities to emerge within single songs.

A lifeline came from an unexpected source: Ginger Baker, the wild-eyed former Cream drummer who had established his own ARC Studios in Lagos. Baker offered Wings use of his better-equipped facility and they recorded portions of Picasso’s Last Words there, with Baker himself contributing percussion. It was a brief respite from EMI’s technical frustrations.

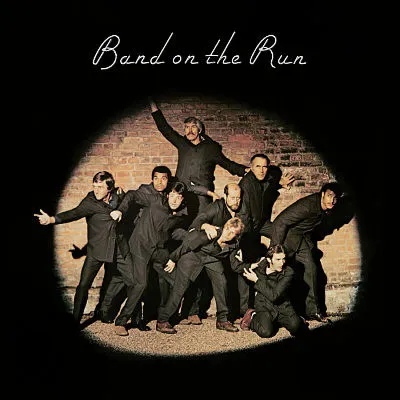

When they finally departed Lagos on September 22nd, the band had completed the basic tracks for what would become Band on the Run. Back in London, final overdubs and orchestral arrangements were added at George Martin’s AIR Studios to polish the raw African recordings into finished songs.

Triumph Against All Odds

The album’s December 1973 release silenced McCartney’s critics emphatically. Songs like Jet, Let Me Roll It and the epic title track possessed an urgency and rawness unlike anything he’d recorded since the Beatles’ final sessions. The title track itself seemed to capture the entire Lagos experience itself in a breathless escape narrative that could have been inspired by their literal need to flee various dangers.

Commercial success followed critical acclaim. Band on the Run would soar to number one in both the US and UK, spawning multiple hit singles and eventually achieving triple platinum status. It won two Grammy Awards and established McCartney’s credibility as a solo artist capable of matching his Beatles legacy.

Paul McCartney’s Telling Resistance to the Suffering Artist Mythology

Yet Paul McCartney himself resists the romantic narrative that hardship forged his masterpiece. He’s consistently downplayed the role of the Lagos difficulties, preferring instead to emphasize the music’s intrinsic qualities rather than its dramatic backstory. “Anything for an easy life with me,” he’s said decades later in rejection of the suffering-artist mythology that critics and fans want to impose on his experience. And on all artists’ experience.

This resistance, however fickle, reveals something essential about Paul McCartney’s character, namely, his preference for craft over drama and his instinct to normalize the extraordinary. He’d rather discuss the technical aspects of recording or the songwriting process than dwell on the adventure story elements that make for better copy.

But the paradox remains tantalizingly unresolved. Paul McCartney never again achieved the artistic heights of Band on the Run, despite recording in far more comfortable circumstances with superior equipment and more cooperative band members. Perhaps the Lagos chaos didn’t create the album’s greatness, but it certainly stripped away everything inessential and left only the pure musical core that had made him legendary in the first place.

The truth may lie somewhere between Paul McCartney’s modesty and the mythology. Lagos didn’t make him a great musician, he already was one when he arrived. But it may have reminded him of what that greatness felt like when pushed to its absolute limits, when comfort and predictability were replaced by necessity and instinct. Whether he admits it or not, Paul McCartney never quite captured that Eko lightning again.