In 1897, British forces invaded the Kingdom of Benin. They burned its capital, exiled its king and stole thousands of sacred bronzes, ivories and regalia. Their goal was simple: erase a thriving African civilization to justify imperial rule. Instead, by looting the Benin Bronzes, they accidentally preserved its legacy forever.

The British called it a “punitive expedition.” The Edo people of Benin called it theft. But history has since delivered the final verdict.

This is the story of how Britain’s plunder backfired spectacularly by turning stolen artefacts into global proof of Africa’s artistic genius.

Dismantling a Kingdom for Profit

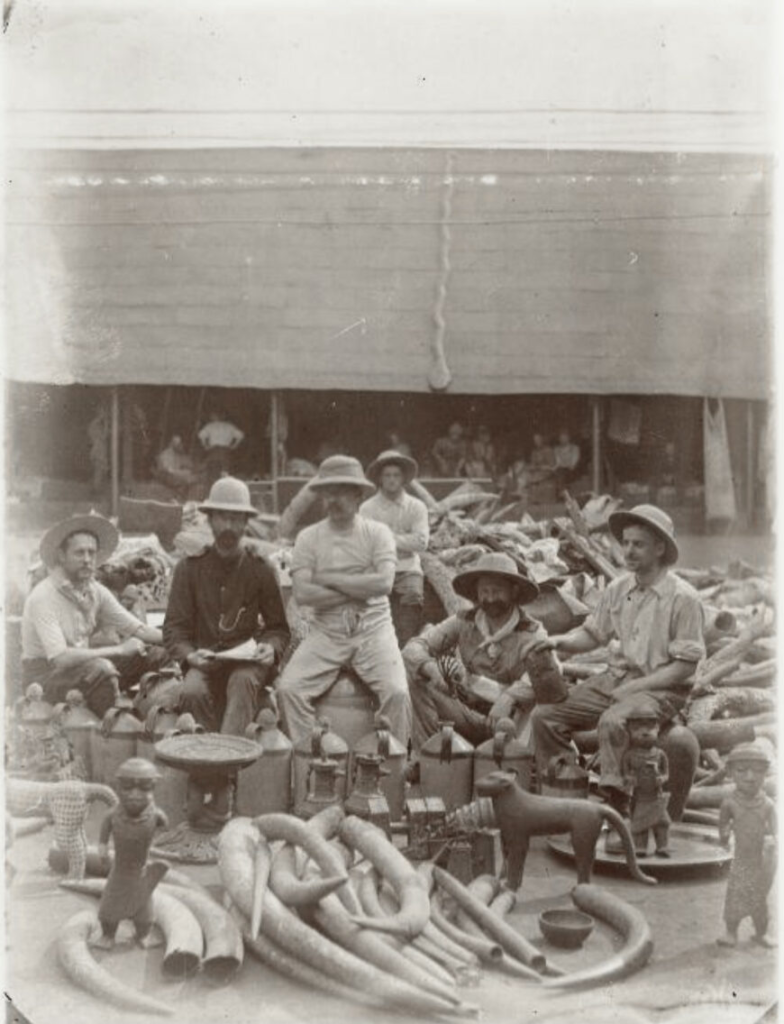

The 1897 assault on Benin City was beyond conquest, it was calculated cultural annihilation. Led by Admiral Harry Rawson with 1,200 troops, the expedition’s true purpose extended far beyond retaliation for the Phillips party’s deaths earlier that year. The British machine-gunned, bombarded and torched villages and towns and indiscriminately massacred countless Edo people between February 9-27. They destroyed buildings, homes and palaces. Sacred sites were desecrated and a sacred tree was blown up. All this was done under the guise of cleansing the city and breaking the power associated with “fetishes” or “juju.”

Private Albert Lucy’s chilling firsthand account captures the systematic nature of this destruction. According to his account: “NEXT DAY WE WENT OUT TO BURN DOWN THE QUEENS PALACE AND OUR BLUEJACKETS WENT OUT AND BURNED THE KINGS PALACE.” The aim of this cultural genocide by fire and bullet was to create a tabula rasa upon which British narratives of being a superior civilization could be inscribed.

During their attack, the British looted an estimated 10,000 objects made of copper alloy, carved and uncarved ivory, works made of wood and coral and human remains. These objects, now known collectively as the Benin “Bronzes,” were originally displayed in the audience courtyard of the Oba’s palace.

Yet in their greed, they overlooked one thing: art doesn’t lie.

The Mistake: Selling the Evidence of A Superior Civilization

To fund their invasion, the British government committed an act of breath-taking short-sightedness: they auctioned the sacred objects in London. It only took time for what seemed like practical economics to become historical self-sabotage. The British Museum received approximately 40% of the looted Benin bronzes. Individual members of the armed forces received some as spoils of war. German museums, American collectors and private buyers across Europe bought up the rest.

This dispersal was the Empire’s greatest blunder. Every bronze plaque sold became a silent testimony to African genius. Every ivory mask displayed contradicted colonial propaganda about “savage” peoples. The British had inadvertently created a global exhibition of their own cultural blindness.

Various museums in London displayed some of the stolen loot within months of their arrival. Charles Hercules Read and Ormonde Maddock Dalton praised the beauty and sophistication of the plaques. They also acknowledged that their makers possessed remarkable experience, knowledge and technical skill on par with Italian Renaissance artists. Yet their racist conditioning prevented them from accepting the obvious truth: these masterpieces were African in origin.

Benin Bronzes: Works of Art That Refused to Lie

The Benin Bronzes possessed a quality that no amount of colonial propaganda could suppress. They were created using advanced lost-wax casting techniques that European smiths had yet to master. These works depicted a sophisticated civilization with complex court rituals, extensive trade networks and remarkable artistic innovation. Two kings, Oba Esigie and his son, Oba Orhogbua commissioned and created the plaques. They chronicled centuries of Edo history, from royal ceremonies to encounters with Portuguese traders. And naturally, they caused a sensation.

The technical mastery was undeniable. These were not crude “fetishes” but sophisticated historical documents cast in bronze. Their naturalistic figures and intricate compositions rivalled the finest Renaissance sculpture. Felix von Luschan, compared them to the work of Italian Renaissance sculptor, Benvenuto Cellini and inadvertently highlighted the absurdity of European assumptions about African capabilities.

Yet colonial scholars, trapped by their own prejudices, performed intellectual contortions to deny African agency. Read and Dalton posited that the fabrication of the plaques could not have been made by the contemporary Edo people, whom they described as “barbarous.” Based on representations of Europeans on the plaques, they speculated all too incorrectly, that the Portuguese taught or helped the Edo to create these works.

According to art historian, Annie E. Coombes: “Intrigued and perplexed that work of such technical expertise and naturalism had been found in such quantities in Africa, the national, local, scientific, and middle-class illustrated press all postulated hypotheses to ‘explain’ the paradox.”

This attribution, or rather explanation, was wrong if not willfully ignorant. As scholar Ese Vivian Odiahi’s research demonstrates, casting was an indigenous art of the Kingdom of Benin. The earliest guild of casters was traceable to the reign of Oba Oguola in the 13th century. This was centuries before Portuguese contact.

The Witnesses Speak their Truth

By the early 20th century, the bronzes had begun their quiet revolution. In museums across Europe and America, they confronted viewers with an uncomfortable truth: the “primitive” Africans had created art that surpassed much of medieval European metalwork. The very objects stolen to justify colonialism were becoming its most eloquent critics.

The irony deepened as European artists discovered African art’s power. The Expressionist movement, Cubism and other modern art forms drew inspiration from African aesthetics, including Benin’s bronze work. The colonizers had unwittingly introduced African genius to the global stage, where it would even influence the very artistic traditions they considered superior.

The Sun Has Long Set on the Empire But Not on the Benin Bronzes

Today, the British Empire lies in history’s dustbin. The Benin Bronzes continue to endure, even transformed from symbols of conquest into icons of cultural vitality. The momentum for repatriation has become unstoppable, driven by the very evidence the colonizers preserved through their greed.

The Netherlands returned 119 Benin Bronzes to Nigeria in February 2025, nearly 130 years after they were stolen, marking the largest physical return of Benin artefacts to Nigeria to date. Germany has also returned hundreds of objects. The University of Iowa Stanley Museum of Art became the first US museum to return looted Benin bronzes to the royal ruler in July 2024.

Nigeria’s national museum commission will be responsible for retrieving and keeping priceless Benin Bronzes. They will share the task with the assent of the royal ruler appointed sole owner and custodian of the objects. The new Edo Museum of West African Art, designed by David Adjaye and being built with financing from the British Museum, would serve as home to these cultural treasures.

The Edo Museum of West African Art (MOWAA) was designed to serve as a permanent home for the Benin Bronzes. By housing these repatriated artefacts, MOWAA hopes to challenge the colonial narrative that Western institutions are the ‘safest’ guardians of African heritage. This mission will not only reclaim Nigeria’s cultural legacy but will also redefine the global narrative surrounding the bronzes.

The Final Irony

Meanwhile, the British Museum clings to its stolen goods like a criminal clutching evidence of his crime. Ironically, they are ‘legally’ prevented from returning them under the British Museum (1963) and Heritage (1983) acts. The institution that claimed to be the world’s safest guardian of cultural heritage has faced embarrassing revelations about missing, stolen and damaged items in its own collection.

Nigeria’s response was devastating in its simplicity: “It’s shocking to hear that the countries and museums that have been telling us that the Benin Bronzes are safer with them are now telling us that they cannot guarantee the safety of these objects.”

The theft has become the teacher. Prince Gregory Akenzua, great-grandson of the exiled Oba Ovonramwen, captures this perfectly: “[The] artwork can be said to represent the history of the Benin people for centuries. It was taken from us. It was like ripping pages out of our history.” But those ripped pages, scattered across the world, became a book that testified against their thieves.

The Benin Bronzes Have At Last Vindicated those Who Made Them

The final twist reveals the expedition’s ultimate failure. The looters thought they were erasing history. Instead, they eternalized it. Every bronze in every museum became a permanent indictment of colonial brutality, a silent witness that no amount of British propaganda could silence.

The Benin Bronzes achieved something remarkable: they turned their own theft into the most powerful argument for African civilization. They proved that great art transcends the intentions of its thieves, that cultural truth outlasts political lies, and that justice, however delayed, finds a way.

The bronzes won.

Today, as artefacts continue to be returned from international markets and private collections, each repatriation is both a homecoming and a reckoning. The British expedition of 1897 intended to destroy a kingdom. Instead, it created the world’s most compelling case for why colonial museums must empty their vaults and return what was never theirs to take.

The thieves have become the disgraced. The “primitive” art has become the teacher. And the Kingdom of Benin, 125 years after its supposed destruction, stands vindicated by the very treasures meant to erase it.