Foreign aid in Africa has always been heavily contested. The obvious reasons is because it sits at the intersection of goodwill and power, survival and sovereignty. As such, it has often been met with either blanket dismissal, or with unquestioned patronage. Here, we analyse foreign aid for what it is: a tool, one whose efficacy depends on how it is wielded, by whom and toward what ends.

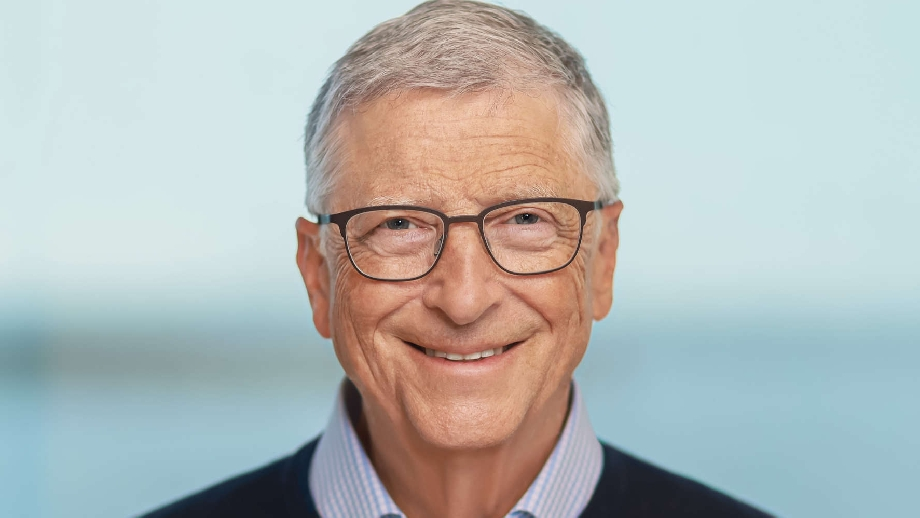

“Sorry, Mr Gates, your billions won’t save Africa”

Standing at the podium of the Nelson Mandela Hall at the African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa, Bill Gates announced that the majority of his $200 billion philanthropic pledge would flow to Africa over the next two decades. “By unleashing human potential through health and education, every country in Africa should be on a path to prosperity,” Gates had declared with characteristic techno-optimism.

This monumental commitment focused on public health, education and agricultural advancement, comes at a time when traditional Western aid is declining, with the U.S. suspending its USAID program and scaling back humanitarian funding. Gates framed his approach as partnership rather than paternalism as a way of emphasizing collaboration with African governments that prioritize their citizens’ wellbeing.

The announcement was followed by a rush from intellectuals and commentators to remind him that foreign aid cannot solve any or all of Africa’s problems. In the most blistering of them, Tafi Mhaka, writing for Al Jazeera, dismissed the announcement wholesale and even accused Gates of ‘white saviourism’ and ‘philanthrocapitalism’.

The Wakanda Fantasy vs. Developmental Realities

The appeal of Wakanda as portrayed in Black Panther is undeniable. It represents an African technological utopia untouched by colonialism or foreign influence, powered by its mythical vibranium. As Magatte Wade noted, Wakanda represented something radical: “Africans as prosperous innovators with cutting-edge technology. There was no foreign aid, no NGOs, no barbaric Africans, no starving Africans, no white saviors in sight”. This vision resonates deeply because it counters the dominant Western narrative of Africa as perpetually needy and dependent.

Wakanda flourishes in isolation, untouched by colonization or foreign dependency; Wakanda takes no aid and Wakanda needs no aid. This image has become emblematic of the aspirations of Africa: to be self-sufficient, modern and powerful on its own terms. But this myth, however empowering, is also deeply misleading.

In reality, many African countries still rely heavily on foreign aid, especially fragile or conflict-affected states. In nations like Somalia, DRC and South Sudan, foreign aid makes up a substantial portion of national GDP. For these countries, aid remains essential for basic survival and day-to-day governance. In these contexts, aid is not a choice, it is a lifeline without which government would cease functioning. In other words, there are no real-world Wakandas and there probably won’t be.

This contrast between our aspiration and reality invites us to acknowledge that foreign aid is still deeply embedded in Africa. And to ask: if so, what are we to make of its moral, political and developmental implications?

Captain Traoré’s Rise and the Reinvention of the Self-Sufficiency Myth

Captain Ibrahim Traoré’s rise in Burkina Faso revived a powerful idea in African politics: the myth of self-sufficiency. His leadership emphasizes resource nationalism, rejection of Western aid and a bold assertion of national sovereignty. This model appeals to those frustrated by long-standing foreign influence and economic dependency. However, this narrative is both aspirational and contested and blends genuine reform with performative defiance.

Traoré’s refusal of IMF and World Bank loans, coupled with his nationalization of his country’s gold mines and establishment of a domestic refinery, echoes Sankara’s 1980s policies of economic autonomy. His rhetoric—”We must not come [to international forums] without having ensured food self-sufficiency for our people”—resonates as a direct challenge to Africa’s historical reliance on foreign aid. By framing Burkina Faso’s struggles as a battle against “imperialist strings,” he positions himself as a disruptor of the aid-dependent status quo.

Traoré’s agricultural reforms have boosted food production by 50%. Regardless, Burkina Faso still remains reliant on Russian grain shipments and foreign expertise for projects like nuclear energy. It also relies on China for energy support. The gold refinery, a flagship project of his regime, still depends on foreign technology. His rejection of the CFA franc as a symbol of French colonial legacy, further fuels the myth, though concrete alternatives still remain unrealized. Then, of course, there is the security situation which still require external intervention.

Traoré’s rise has amplified the self-sufficiency myth by blending Sankarist idealism with anti-Western pragmatism. However, his model is less a clean break from dependency on foreign aid than a recalibration. In other words, he merely replaced Western patrons with Eastern ones, using sovereignty as a political weapon. The deeper lesson is that self-reliance, though inspiring, cannot rest on symbolism alone. It requires strong institutions, which Burkina Faso is still working to build. Since most African states remain in this phase, they will still need some form of foreign aid.

Three Critiques of Foreign Aid in Africa

Broadly speaking, there are three dominant critiques of foreign aid in Africa, each with distinct emotional tones and political implications.

1. The Cynical View

This view of foreign aid in Africa sees it as a smokescreen for neo-colonial control and manipulation. Aid, in this framework, is less about altruism and more about influence. It allows powerful states and institutions, such as the U.S., China, the IMF and the World Bank, to dictate policy directions in recipient countries. By attaching conditionalities to loans or grants, for example, requiring privatization or fiscal austerity, donors are said to infringe upon national sovereignty. Aid becomes less a gift than a leash.

There are numerous historical instances in support of this view, like the SAP of the 1980s that wiped out entire industries in Africa and dragged many Third World countries into unpayable debt. The problem with this view is that it can devolve into an ideological position.

Yet while this perspective raises valid concerns, it can easily devolve into ideological absolutism that reduces all forms of aid to acts of manipulation. It risks ignoring the nuances between humanitarian aid, development assistance, multilateral versus bilateral mechanisms and aid shaped by African ownership. By treating all aid as suspect, it closes off the possibility of reforming aid to serve African priorities.

2. The Self-Righteous View

Here, the critique turns inward. This view, often purely ideological and expressed by members of the African intelligentsia or diaspora or pan-African thinkers, argues that accepting foreign aid is itself a sign of national failure or even weakness. It expresses a belief that African states ought to refuse all assistance on principle and to “stand on their own feet,” even if it means hardship. While emotionally powerful, this perspective often overlooks the historical and structural inequalities that necessitate aid in the first place.

This position, too, can slip into ideological rigidity. It risks becoming a purist stance that values symbolism over substance. While self-reliance is a noble goal, many states, especially those facing conflict, climate shocks, or collapsing infrastructure, cannot realistically achieve it in the short term. To reject all forms of aid on principle may sound defiant, but in practice it can only amount to negligence, especially for vulnerable populations who rely on aid for health, food security and emergency response.

3. The Righteous Critique

The most balanced and useful critique of aid comes from those who acknowledge both its necessity and its problems. These critics highlight the real issues with foreign aid in Africa: corruption, misallocation, donor-driven agendas, dependency and the undermining of domestic institutions. Yet they do not argue that aid should end. Instead, they propose ways to make aid more accountable, effective and developmental.

This view call to mind programs funded by aid, such as PEPFAR that has saved 17 million lives from HIV/AIDS and enabled 2.4 million babies to be born HIV-free, the Global Fund and GAVI, which have dramatically reduced deaths from HIV, tuberculosis and malaria across Africa. They cite vaccination campaigns have saved millions of lives. They also call to mind aid from China and multilateral agencies that has supported the construction of roads, railways, ports and energy systems across Africa. These are foundational to economic activity. Then there are countless schools and clean water systems have been built using donor funds, especially in rural areas where state presence is minimal.

Indeed, the Gates Foundation itself has played a leading role in financing health infrastructure, agricultural research and digital identity systems across the continent. Thanks to foreign aid, global health has achieved historic victories: smallpox was eradicated, and polio has been eliminated in all but two countries. Between 2000 and 2017, foreign-funded programs helped cut deaths from malaria, and reduced maternal, child, and infant mortality rates by half across many parts of Africa and the Global South. Foreign aid has also helped reduce poverty drastically.

Yet, despite these gains, the criticisms of those who hold this view remain potent.

They acknowledge that foreign aid can inadvertently create perverse incentives. Governments that rely on foreign donors may feel less pressure to tax their citizens or deliver public services. This can erode the social contract between rulers and the ruled and create what economists can ‘a rentier state,’ or a state whose economic survival does not depend on its taxpayers.

Moreover, aid often flows through elite networks. Thus, it can always be siphoned off by corrupt officials or used to finance patronage systems. In the worst cases, aid enables fragile states to delay the hard work of reform by outsourcing responsibility to external actors. In all, dependency becomes a danger when countries begin to treat aid not as a supplement to its own efforts but as a substitute for governance.

The Core of the Problem Remains Governance

This leads us to the crux of the issue. In the first place, foreign aid exists primarily due to gaps in governance. And the only way to properly manage foreign aid, in view of ultimately eliminating it is by entrenching good governance. Since improving governance takes time, foreign aid remains a necessity in the short term. This should not constitute an argument. Whether aid helps or harms is the argument. And this depends largely on how it is used. Institutions that are transparent, accountable and responsive have shown that they can use aid in transformative ways. But when institutions are weak or predatory, they are more likely to waste aid or worse still, weaponize it.

In essence, we should not judge foreign aid in isolation; it operates within a broader political economy. A well-governed society can use aid strategically to build infrastructure, train workers and support innovation ahead of building resilience and ultimately eliminating aid entirely. A poorly governed one will likely use it to enrich elites or postpone reform and perpetuate the flow of aid.

Bill Gates’s $200 billion pledge may or may not succeed. But it frames the right questions. Africa’s challenge is not to reject aid out of pride, nor to embrace it out of habit, but to use it wisely and build institutions capable of standing alone. While it is essential for addressing immediate crises and building human capital, aid alone cannot create prosperous societies. The Wakanda ideal, though economically unrealistic, rightly challenges Africa to envision self-sufficient futures. But ultimately, it is building up the economy through sustained governance reforms and strategic partnerships that will help Africa eventually close the gaps on foreign aid.