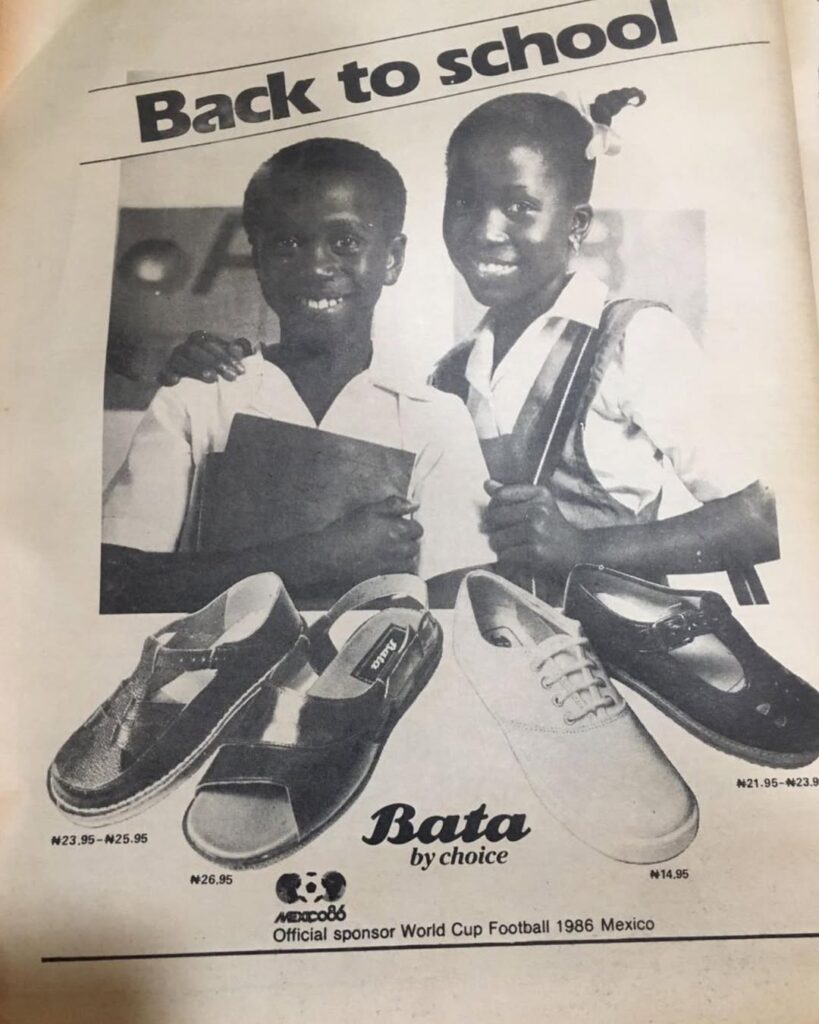

For generations of Nigerians who came of age in the 1970s and 1980s, the mention of “Cortina” evokes something deeper than a mere brand name. Bata shoes were symbols of durability, status, and childhood identity, thanks to a democratic brand that cut across all social classes.

The Empire That Started in a Shop

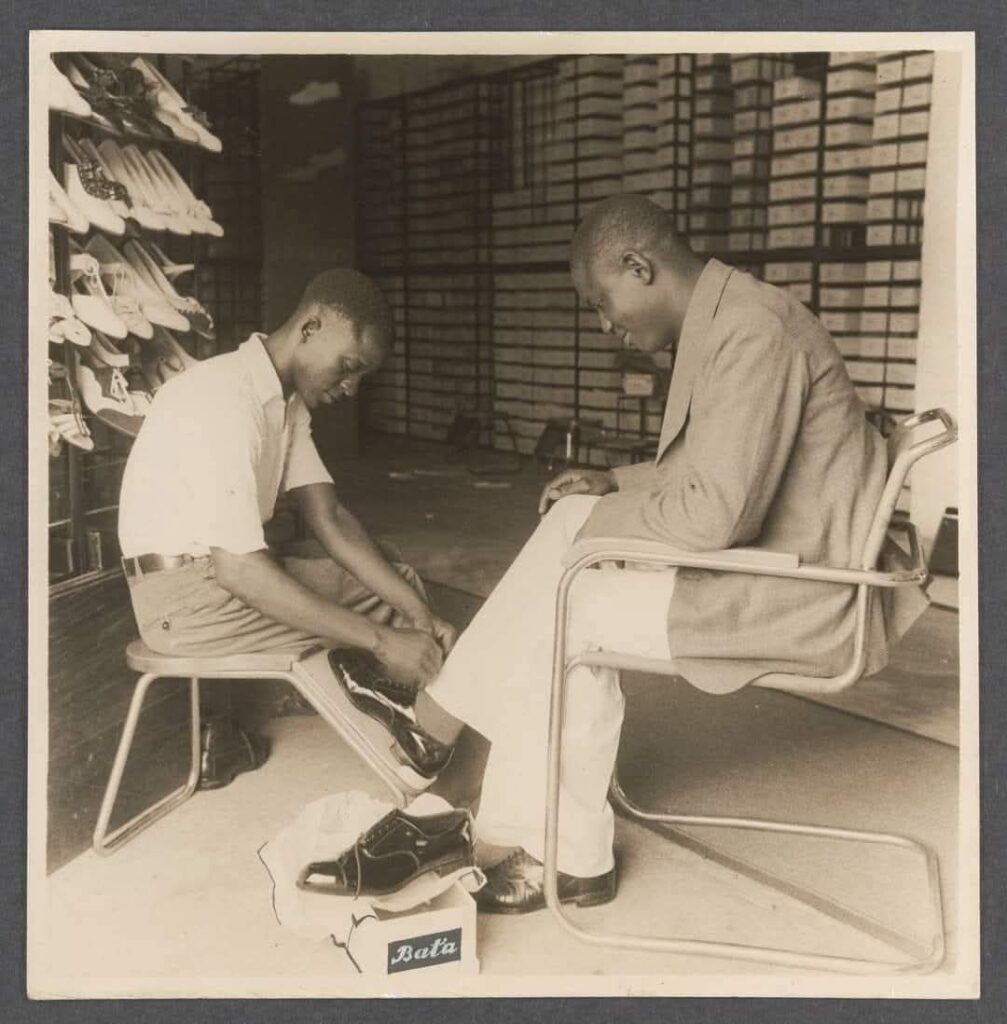

The Bata story in Nigeria began modestly in 1932 when the first Bata shop opened its doors in Lagos. By this time, what had started as a simple retail venture in Zlín, then part of Austria-Hungary, had grown into a manufacturing empire. The vision belonged to Thomas Bata, a Czechoslovakian entrepreneur who revolutionized shoemaking through the technology of the shoe conveyor that did for footwear what Henry Ford had done for automobiles.

By 1938, Bata had established nine stores across Nigeria, from Lagos to Onitsha, creating a distribution network that would become the envy of competitors. But the real transformation came in 1965 when Bata opened its modern shoe factory, turning Nigeria from a market into a manufacturing hub. The crown jewel was the Ojota factory, where raw materials were transformed into the sturdy sandals that would become household names. The administrative headquarters at No. 78 Broad Street coordinated what had become a vertically integrated operation spanning the entire country.

Cortina sandals were engineered for the Nigerian environment. They were sturdy enough to withstand the rough play of schoolchildren, yet affordable enough for average families. According to nostalgia accounts, “for every household with primary and secondary school children, there must be at least a pair of Cortina shoes for each of the children.” They were ubiquitous, reliable, and utterly Nigerian.

Battling Giants

Bata’s dominance didn’t go unchallenged. The Nigerian footwear market of the 1970s and 1980s witnessed fierce competition between manufacturing giants. Lennards Shoes, established in 1953 as a subsidiary of Greenlees Lennards Limited of England, provided formidable competition. In a fascinating example of competitors collaborating even as they competed, Lennards strategically partnered with local manufacturers, including contract manufacturing arrangements with Bata’s own Ojota factory.

Limson Shoes, owned by Alhaji Alimi, was yet another significant player in this golden age. These companies, along with smaller players, created a vibrant ecosystem where local manufacturing thrived and Nigerian consumers had genuine choices between quality domestic products. The success reflected a broader truth: when the right policies, infrastructure, and vision aligned, Nigerian businesses could compete globally.

The Perfect Storm

The 1980s brought challenges that would test the resilience of Nigeria’s manufacturing sector. The introduction of the Structural Adjustment Program in July 1986 marked a turning point. Originally intended as a short-term reform, SAP aimed to reduce import dependence and improve Nigeria’s non-oil export base. However, its implementation created unintended consequences that devastated local manufacturers.

As foreign exchange became scarce, companies that had built their success on imported raw materials found themselves in crisis. The forex challenge made importation extremely difficult, and the few raw materials that could be imported became too expensive. For Bata Shoes, this period marked the beginning of a decline that would culminate in the closure of its Nigerian operations around 2000.

The company faced a perfect storm: harsh government policies, increased competition from inferior locally-made shoes from Aba, and imported second-hand footwear that flooded the market. The factory that had once produced millions of pairs of shoes annually gradually reduced operations before eventually shutting down.

Shadows in the Boardroom

Adding to the economic turbulence were allegations of internal turmoil. In 1997, Chief (Mrs.) Olakunri, then chairman of Bata Nigeria Plc, allegedly orchestrated the transfer of 40% of Bata Overseas Trading Company’s shares into her own control using offshore shell companies registered in the U.K. and Panama, all without shareholder or SEC approval.

According to these allegations, she used these shares as collateral to secure loans, effectively mortgaging assets held in trust for approximately 15,000 investors. What followed was a deterioration of corporate transparency, Annual General Meetings were suspended, import contracts were allegedly inflated, and financial records grew increasingly opaque. When Deloitte, one of Nigeria’s most respected auditing firms, examined the books, they disclaimed the financial statements and cited major irregularities.

The implications were enormous. Workers reported unpaid tax deductions and withheld cooperative savings. Regulatory institutions remained passive, ignoring repeated petitions and allowing the company to be quietly delisted from the Nigerian Stock Exchange.

Chief Olutoyin Olusola Olakunri, notably Nigeria’s first female Chartered Accountant and first female president of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nigeria, passed away in 2018. The allegations, were however, never proven in court and remain a dark footnote to Bata’s Nigerian chapter.

A Second Coming

In late 2019, nearly two decades after closing its operations, Bata returned to Nigeria with a new factory in Abuja. The new facility, capable of producing over 500,000 shoes annually and employing roughly 120 people, represents both continuity and change.

Bertram Dozie, the chief executive of the new Bata Nigeria franchise, said Bata still saw “glaring” opportunities in Africa’s most populous nation. The company now sells everything from strappy heels and protective work boots to the black leather school shoes that continue to evoke memories of the Cortina era.

The return reflects broader changes in Nigeria’s manufacturing landscape. Import restrictions on shoes implemented in 2007 as part of the “Made in Nigeria” agenda have begun showing results. Nigerian footwear imports fell from $180 million in 2010 to $100 million in 2018, creating space for local manufacturers to reclaim market share.

The Legacy Endures

For millions of Nigerians, Bata remains embedded in personal histories. The durability of Cortina sandals became metaphorical for the resilience required to navigate Nigeria’s economic challenges. Parents who wore Cortina to school in the 1970s and 1980s now seek similar quality and value for their own children.

Today, when young Nigerians see the new Bata shoes in stores, they’re touching a piece of Nigeria’s industrial history. Whether the new Bata can recapture the magic of the Cortina era remains to be seen. But its return represents something powerful: the enduring belief that with the right vision, Nigerian manufacturing can once again compete with the best in the world.

The story of Bata is ultimately a story about Nigeria itself; a tale of promise, turbulence, resilience, and the hope that what was once great can be great again.