Colonial Nigeria was marked by its own policies of racial segregation. Ikoyi was an epitome of this: it was designated as “European reservations” and reserved for white officials and businessmen. Nigerians were not allowed to live there. The MacGregor Canal was built, in part, to separate Ikoyi from the rest of Lagos. Public facilities and hotels were also racially segregated, with native Nigerians unable to access or use them.

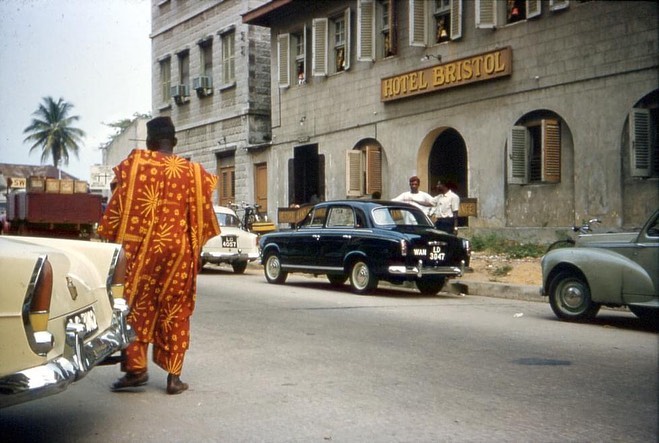

However, a seemingly minor incident happened at Bristol Hotel, Ikoyi, in 1947. It would spark a protest movement that nipped this evil in the bud and altered the course of Nigerian history.

The Bristol Hotel Incident: A Match to the Powder Keg

In April 1947, a distinguished Black West Indies official from the Colonial Service in London stepped into the Bristol Hotel. The prestigious hotel on Martin Street, Lagos was owned by Greek proprietors and was renowned for its strict “Whites Only” policy. ,The visitor’s name was Ivor Cummings. He was visiting on official business.

The colonial government had arranged for Cummings to be accommodated at the Bristol Hotel. However, when Mr. Cummings arrived, the hotel management was stunned to discover that he was instead Black. They had assumed that he was white due to his British-sounding name. Despite Mr Cummings’ status as a British colonial official, the hotel immediately revoked his reservation on the basis of their “Whites Only” policy.

News of this snub spread rapidly through Lagos. For the Nigerian educated elite and youth who had been simmering with resentment against colonial racism, this was the final straw. The day after Cummings was turned away, outraged young Lagosians stormed the Bristol Hotel and vandalized its premises in protest.

The Nigerian press seized upon the incident. Newspapers like the West African Pilot and Daily Service condemned the discrimination. Run by nationalists, they used it to amplify calls for freedom from colonial rule and an end to racial segregation. What might have been dismissed as an isolated incident would inadvertently lead to the end of the segregation policy.

Source: USC Digital Library

Original Snapshot taken by Eldred Echols and Boyd Resse during their 1950 visit to Lagos.

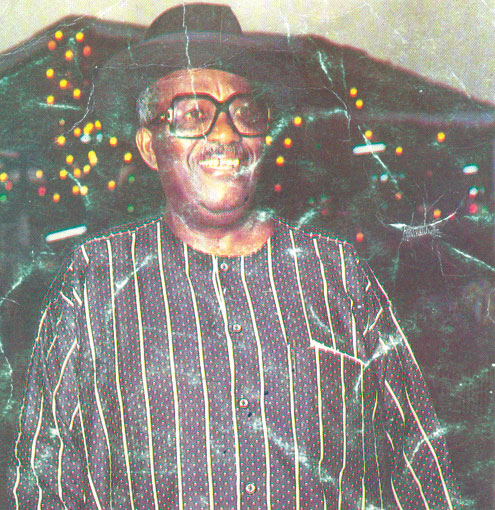

Alfred Rewane Steps Forward

The momentum from the 1947 incident continued into 1948, when Alfred Rewane, a prominent Nigerian civil rights leader and businessman, took decisive action. Born in Warri in 1918, Rewane had worked with the United African Company before venturing into the timber industry and becoming a close associate of Chief Obafemi Awolowo.

Rewane, a member of the prestigious Island Club, led a sit-in protest at the Bristol Hotel. He was joined by other notable Nigerians, including Olugbaike, a trade unionist; Milton Macaulay; Prince Adeleke Adedoyin; and Adeyemo Alakija. Their peaceful but powerful demonstration directly challenged the hotel’s racist policies and, by extension, the colonial authorities themselves.

The sit-in garnered significant attention and placed tremendous pressure on colonial officials still reeling from the violent protests of the previous year. Under mounting pressure, Governor Arthur Richards issued a ban on all forms of racial discrimination in public facilities throughout Nigeria in what was a watershed moment that was decisive for the rest of Nigeria’s history.

Ikoyi: White Man’s Territory

To understand the full significance of the Bristol Hotel protests, we must examine Ikoyi, which epitomized racial segregation in colonial Nigeria.

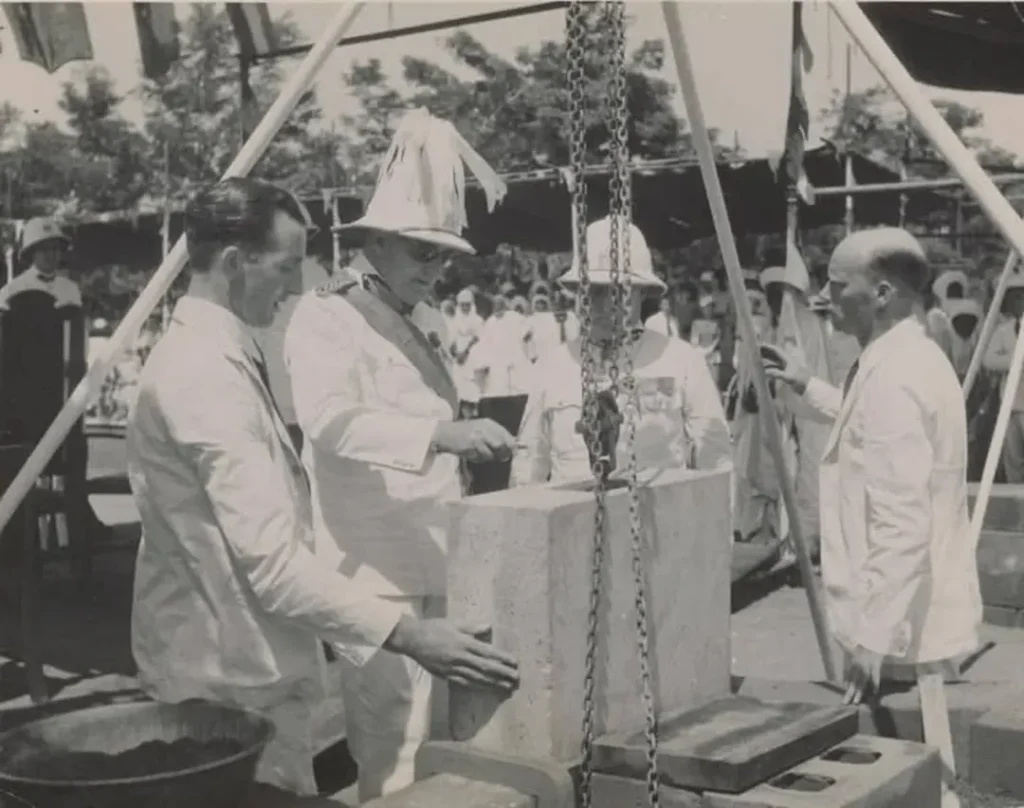

In 1919, Governor Frederick Lugard complained that in Lagos, “the residences of Europeans and natives are… hopelessly intermixed.” That same year, construction began on the Ikoyi reservation, an exclusive residential area for white officials and Western businessmen.

This designation of Ikoyi was controversial from the start. The colonial government claimed ownership through the 1908 Ikoyi Lands Ordinance. The Ordinance required landowners to register within a year or forfeit their land. The Onikoyi family challenged this ruling in the courts during the 1920s. They would ultimately settle for token compensation in what was a textbook example of how colonial authorities exploited local systems to steal their land.

Ikoyi was physically separated from the rest of Lagos by the MacGregor Canal, which again reinforced its exclusivity. The area was characterised by superior urban planning, sanitation and amenities that were unavailable to ordinary Nigerians. Access to Ikoyi was strictly controlled, with property leases containing clauses that prohibited subletting to non-Europeans. African domestic servants could live in separate quarters within European households, but African professionals and elites were systematically excluded.

Ikoyi remained officially designated as a “European reservation” until 1938, when British officials, sensing growing resistance to explicit racial segregation, rebranded it with the racially neutral term “government residential area” (or “GRA”). Today, such GRAs exist everywhere across Nigeria. Also, the European hospital in Lagos (now Military Hospital) and European Club at Ikoyi were both renamed Creek Hospital and Ikoyi Club, respectively. But this change was cosmetic. It did little to alter the reality that Ikoyi remained overwhelmingly white.

The New Youth Movement Against Segregation

The Bristol Hotel protests were part of a larger movement against racial segregation and colonial oppression. At the same time as the hotel incidents, Anthony Enahoro, a journalist and future nationalist leader, gave a fiery speech at Tom Jones Hall. In the speech, he advocated for revolution against foreign rule. He was arrested and convicted of sedition. This showed the growing tensions between Nigerians and colonial authorities that further fuelled the independence movement.

Educated Nigerians played the key role in challenging segregation by using their influence in the colonial Legislative Council and the press. From the late 1930s, they persistently questioned their exclusion from senior civil service positions. These positions were known as “European posts” and were accompanied by reserved housing. Nigerian Civil Service Union members and trade unions demanded equal rights and privileges, including access to these reserved housing in government quarters befitting their official positions.

Their persistence yielded results. By 1949, Nigerian members of the Legislative Council were granted housing accommodations in Ikoyi during council sessions. And the colonial government would construct 24 flats for Nigerian legislators. This development marked the beginning of the integration of Africans into previously exclusive European enclaves.

The Legacy and Impact of the Bristol Hotel Protests

The protests at the Bristol Hotel helped prevent Nigeria from going down the path that South Africa took. In 1948, as Nigeria was moving away from explicit racial segregation, South Africa was institutionalizing apartheid, a comprehensive system of legal racial segregation that would oppress non-whites for decades.

The Bristol Hotel protests forced policy changes that made it impossible for a similar system to take root in Nigeria. These changes didn’t immediately or totally dismantle deeply ingrained racial hierarchies, as many Nigerians who moved into formerly segregated areas reported feelings of isolation, as the social fabric remained dominated by European norms. Even as late as the 1950s, Chinua Achebe, who moved to Ikoyi in 1954, would later write in No Longer at Ease that “Ikoyi was like a graveyard. It had no corporate life, at any rate for those Africans who lived there.”

Yet the transition was significant and decisive for Nigeria’s history. By the 1950s, Nigerians held senior civil service posts and accessed previously restricted spaces, though tacit racialization persisted. The protests and subsequent policy changes laid the groundwork for a more inclusive Nigeria. They helped dismantle the institutionalization of racial segregation in public spaces, institutions and residential areas.

The Power of Resistance

The Bristol Hotel protests of 1947 and 1948 are a pivotal moment in Nigeria’s history. To be sure, South Africa’s context differs significantly from Nigeria’s. Regardless, if Nigeria had allowed these policies, they would have deepened the colonializers’ power and would have delegitimised our aspirations for independence. The resistance was a pre-emptive strike against a racial caste system that could have calcified Nigeria’s colonial divisions into something far more enduring and destructive like South Africa’s.

Alfred Rewane and others who led the resistance understood that challenging racial segregation was essential to creating a more equitable society. Their courage and determination ensured that Nigeria would not follow South Africa into institutionalizing racial segregation. Beyond his involvement in the 1948 protest, Rewane remained an advocate for democratic rights. He was instrumental in supporting pro-democracy movements during military regimes. Also, his business acumen led to the discovery of limestone deposits in Nigeria. Tragically, his commitment to democracy made him a target, leading to his assassination in 1995.

The legacy of these protests lives on in modern Nigeria. And though it does not command a significant space in our collective memory, it is still, nonetheless, a definitive chapter in Africa’s long struggle for both racial and political equality.

Primary Source: State, Urban Space, Race: Late Colonialism and Segregation at the Ikoyi Reservation in Lagos, Nigeria by Tim Livsey.