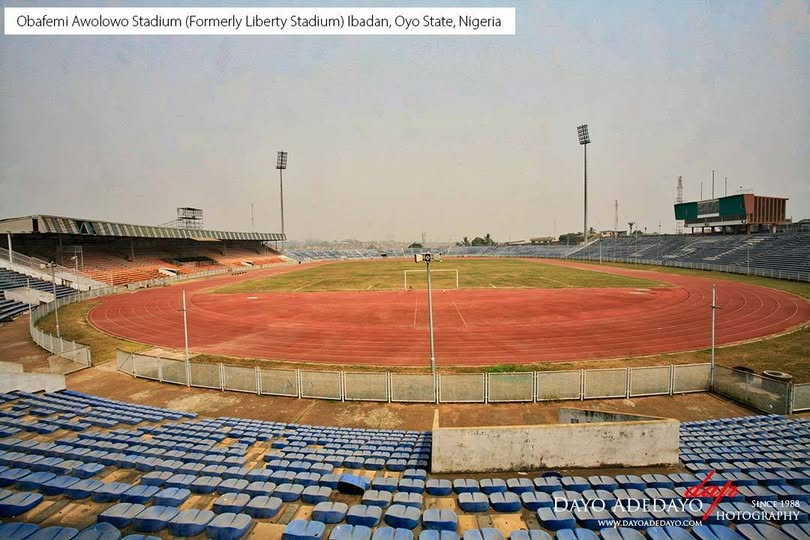

Liberty Stadium, now Obafemi Awolowo Stadium, Nigeria’s first modern stadium, was once the crown jewel of West African sports infrastructure. It was hailed as one of the finest in the world and drew comparisons to London’s Wembley. It hosted Nigeria’s first football match under floodlights and one of the earliest world boxing title fights ever held on African soil.

For decades, it was a magnet for athletes and spectators across the continent and a symbol of Western Nigeria’s bold aspirations. Today, it sits in quiet decay. Its once-pristine fields overrun by weeds and its corners colonized by reptiles.

The Origins of the Stadium

The story of Liberty Stadium begins in 1957 when Chief Gabriel Akintola Deko, then Minister of Agriculture of the Western Region under Chief Awolowo’s administration, conceived a world-class sporting facility. To bring the vision to life, the Western Region Government established a committee comprising four of its ministers, officials from the Ministry of Works and representatives from the athletics association.

Developers chose Ring Road in Ibadan as the site for the stadium. Chartered architect J.E.K. Harrison, working with the Western Region’s Ministry of Works and Transport, designed the stadium. Construction began with a foundation-laying ceremony on March 11, 1958, and workers completed the project in just over two years, finishing in time for Nigeria’s 1960 independence celebrations.

Africa’s Premier Sporting Arena

Liberty Stadium’s opening in September 1960 coincided with Nigeria’s independence celebrations. This coincidence gave it the name, Liberty Stadium. It was built on 75 acres of hillside land, with the main bowl occupying 40 acres. Construction cost was £521,050, with an additional £38,000 spent on land acquisition and another £35,000 on constructing the approach road.

According to the standards of the time, the 25,000-capacity stadium was a marvel of engineering. Foreign visitors who attended its opening described it as “another Wembley,” in comparison to London’s iconic stadium. The comparison was not an exaggeration. Liberty Stadium featured state-of-the-art facilities, including a sophisticated underground drainage system capable of bearing away the heaviest of rainstorms without the risk of flooding.

Breaking the Ground

To allow proceedings at night, the main bowl had floodlights, the first of its kind in Nigeria. And on October 11, 1960, it would host the first football match played in Nigeria under the floodlights. The match was between the region’s team, West Rovers and Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau). It had Chief Obafemi Awolowo as the special guest. The match ended in a 3-2 victory for the home team. The regional government would later introduce a competition that took its name from the floodlights, ‘Floodlit Festival Cup’. The Cup hosted teams in Lagos, northeast and western parts of the country. The Nigerian Tobacco Company (NTC) donated a trophy for the tournament.

The stadium’s facilities were comprehensive by the best standards. Beyond the main football pitch with its floodlights, it had indoor sports halls, swimming pools and courts for tennis, volleyball, handball, basketball and hockey. Completing the impressive complex was a cricket pitch and three additional football practice fields, each with its own floodlights.

Glory Days

The stadium’s initial management was entrusted to Joseph Ogunyemi, the first Nigerian ever to be trained and appointed as a stadium manager. Prior to his appointment in December 1959, Ogunyemi had undergone 18 months of specialized training at prestigious venues including White City Stadium in London, Wembley Stadium and London University’s athletics ground. His apprenticeship included courses in Paris and at Berlin’s Olympic Stadium. Under his stewardship, the stadium maintained its world-class standards.

Throughout the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, Liberty Stadium was the epicentre of Nigerian sports. In 1962, it shot Nigeria into global boxing fame when it hosted the first world boxing title fight in Africa. During the historic bout, Nigeria’s Dick Tiger defeated America’s Gene Fullmer to claim the world middleweight boxing title. This event brought global media attention to Ibadan and Western Nigeria and showcased the region’s rapid development.

With the passage of years, the stadium hosted numerous significant international football matches. It drew crowds to group matches during the 1980 Africa Cup of Nations and the semi-final between Algeria and Egypt. In 1999, it was one of nine stadiums that hosted Nigeria 99′, the FIFA World Youth Championship. It welcomed all Group C matches for the tournament, a Round of 16 match and a quarterfinal match.

For Nigerian athletes of the era, playing at Liberty Stadium was an achievement. Former Green Eagles winger Adegoke Adelabu would tell The Guardian: “In our days, it was a dream for anyone to play at the Liberty Stadium. The complex was so good that even players from different parts of Africa wanted to visit it.”

Segun ‘Mathematical’ Odegbami, former Green Eagles captain, played his first international match at Liberty Stadium in 1973 against the Central African Republic in preparation for the All-Africa Games. He also reminisced to The Guardian about its status: “Liberty Stadium was a great showpiece because its architecture was unique. Some of its facilities were world-class and it was a local tourist attraction for visitors.”

The People’s Stadium

Beyond hosting elite competitions, Liberty Stadium served as a vibrant community hub. People came on excursions to tour its facilities. They would wait to witness the well-choreographed watering system that maintained the lush green turf. The stadium attracted thousands of spectators daily who came just to watch training sessions of star athletes.

Every morning and evening, youths from across the state would flock to the stadium to watch national stars train. The complex became a centre for sports development, with many of Nigeria’s future champions cutting their teeth on its facilities. The stadium also functioned as a social centre. Even today, despite its sorry state, the stadium remains a place for relaxation, especially in the evenings when bar and restaurant operators serve traditional delicacies.

The Decline

The taking over of the stadium by the Federal Government in 1976 would mark the beginning of its decline. Without the regional pride and interest that had sustained its excellence, the stadium began to languish under bureaucratic inertia and neglect. The last time the national team played at the stadium was on July 9, 1983. Nigeria would defeat Togo 2-1 in a Los Angeles ’84 Olympic Games qualifying match.

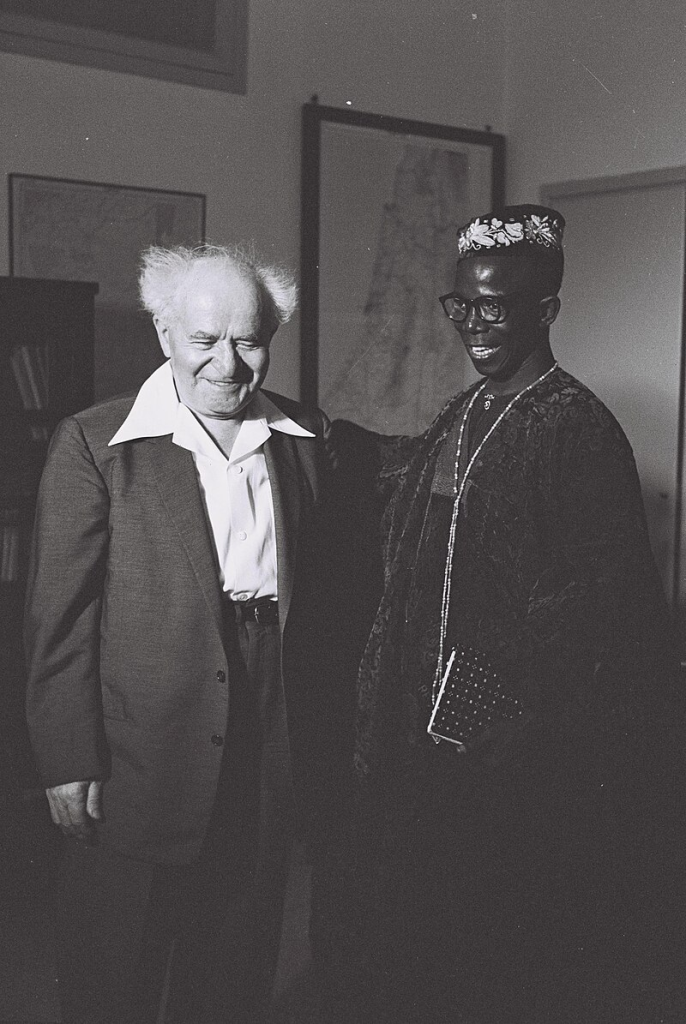

An Israeli firm was contracted to renovate the stadium during preparations for the 1995 FIFA World Youth Championship. According to Odegbami speaking to The Guardian, the engineers admitted that the existing drainage system was superior to the untested ‘Cell’ underground watering system they had been contracted to install. Despite their advice against proceeding with excavation and demolition, Nigerian sports administrators insisted they go ahead and retrofit the system.

“In ‘renovating’ the stadium, the Israelis completely destroyed it,” Odegbami lamented. “Since that ill-informed deliberate destructive act, the Stadium has remained prostrate, its painted walls a shell and a constant and painful reminder of what was once one of the best in the world.”

By 2018, wrote The Guardian, the stadium was in a worrisome state. The once-impeccable pitch had become unusable “even for a primary school soccer competition.” Part of the roof over the state box had been blown off. The tartan track, which had been partially removed in 2014 with promises of replacement, remained unfinished. The swimming pools had been abandoned and overtaken by dirt, with only a small pool operated by a private investor functioning mainly for children. Also, the spectators’ stand of the swimming pool had lost its roof, with its stairs having fallen off. The main pool had turned black, overgrown by algae, with plastic bottles and other waste materials floating on its surface.

The Legacy Lives On

Despite years of neglect, Liberty Stadium’s legacy remains intact. On November 10, 2010, President Goodluck Jonathan renamed it Obafemi Awolowo Stadium to honour the visionary leadership that brought it to life. Even in its decayed state, the stadium continues to be of use to the community. Young footballers train on its grounds daily and adults use the privately run gymnasium to stay fit.

It also invites tennis enthusiasts who make use of the five courts maintained by the Obafemi Awolowo Tennis Club. But just like the groundnut pyramids and the Cocoa House, Liberty Stadium is one of too many metaphors for Nigeria itself: a nation of immense promise dimmed by poor stewardship.